Trolleys, veils, prisoners Hidde de Vries • 5-11-2018 • Accessibility Club Conference, Berlin

Slide 1

Slide 2

Hello! I am a front-end developer, spending most of my time at Mozilla in their Open Innovation team, and some of it at the Dutch City of The Hague, as an accessibility person, amongst other things.

Slide 3

Before I became a web developer, I studied Philosophy. This Rennaissance painting by Raphael shows some very ancient philosophers. One thing thing that philosophy students learn a lot about is reasons, coming up with good reasons for doing things. We do this all the time, when we try and make the case for accessibility at a client or project.

Slide 4

Let's look at some reasons for making accessible sites. There is the technical reason: semantic code is easier to work with, it is how the web is by default, et cetera. There are legal reasons too, WCAG2.1 is pretty much compulsory to comply with if you're a government in Europe. You can have business arguments, too: if your site works for more people, you can earn more money. But the argument we'll look at today is the moral argument.

Slide 5

Ethics and morality, they're technically not exactly the same, but I'll use them interchangeably today. So, ethics is about these questions: how to live, what to do and how we want our world shaped. You might wonder what all this has to do with our field? Well…

Slide 6

I can give lots of examples, what about Facebook? They hugely influence how we live, and what our world is shaped like. There are lots of ethical questions to be asked.

Slide 7

So these are the three questions ethics is concerned with.

Slide 8

In this talk, I'll focus on the three main branches of moral philosophy, which are centuries apart in the history, but that's ok. We'll look at virtue ethics, duty ethics and utilitarianism.

Slide 9

Let's start with Aristotle. He was the first person to ever write about moral philosophy, it was all about other things like natural science before that. His branch of ethics is called virtue ethics.

Slide 10

Important in virtue ethics, is that there are no rules to be learned, it is about developing your character in a way that lets you make the right decisions and do the right actions.

Slide 11

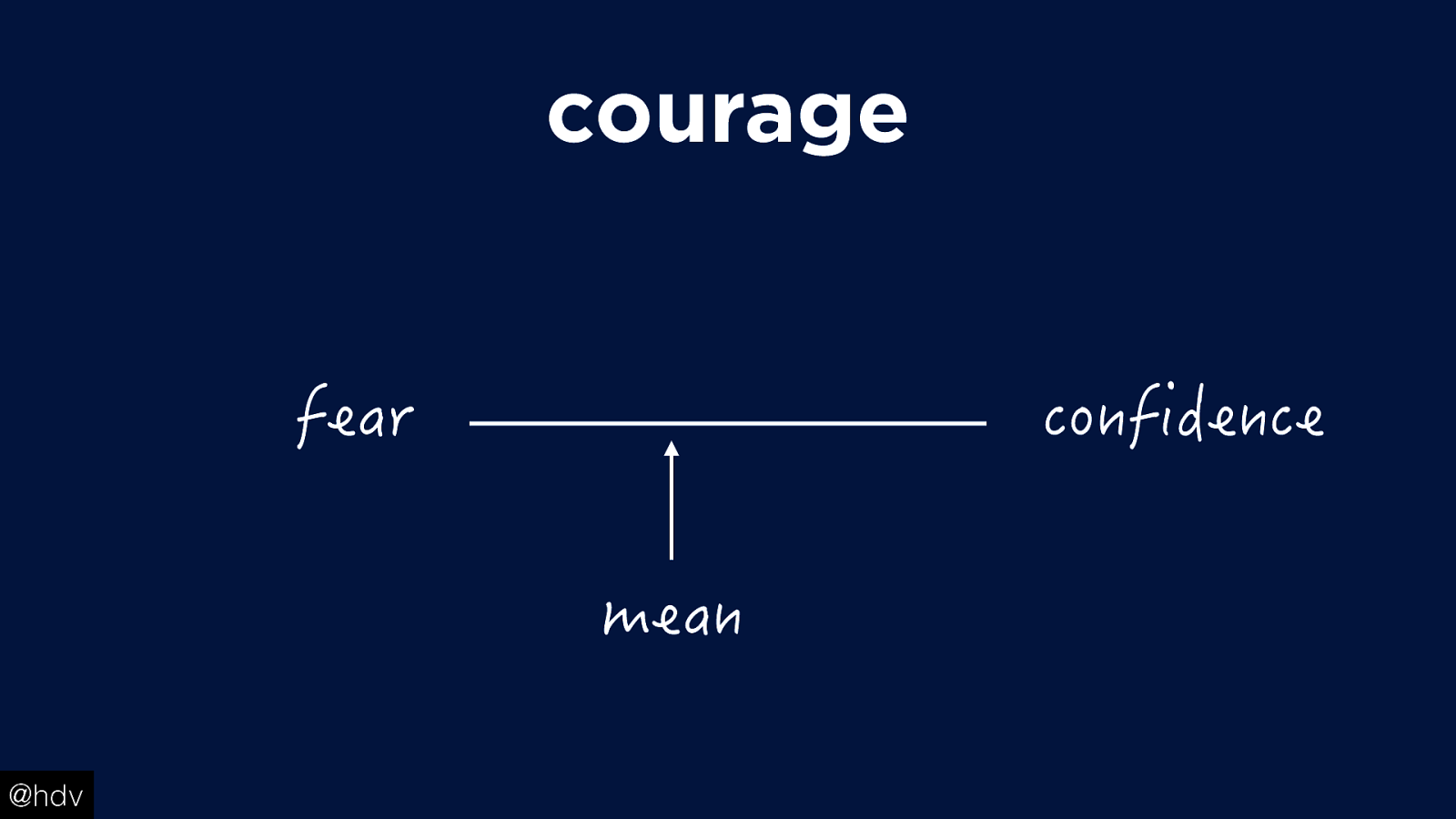

The different character traits are also called virtues, for example honesty, moderation, generosity, friendliness and courage.

Slide 12

You don't get virtuous by chance, it is hard work and a bit like acquiring a skill.

Slide 13

It's about being somewhere on the line between two extremes, and figuring out where to be on that line. That's where the skill comes in.

Slide 14

Knowing where to be is about finding the best mean.

Slide 15

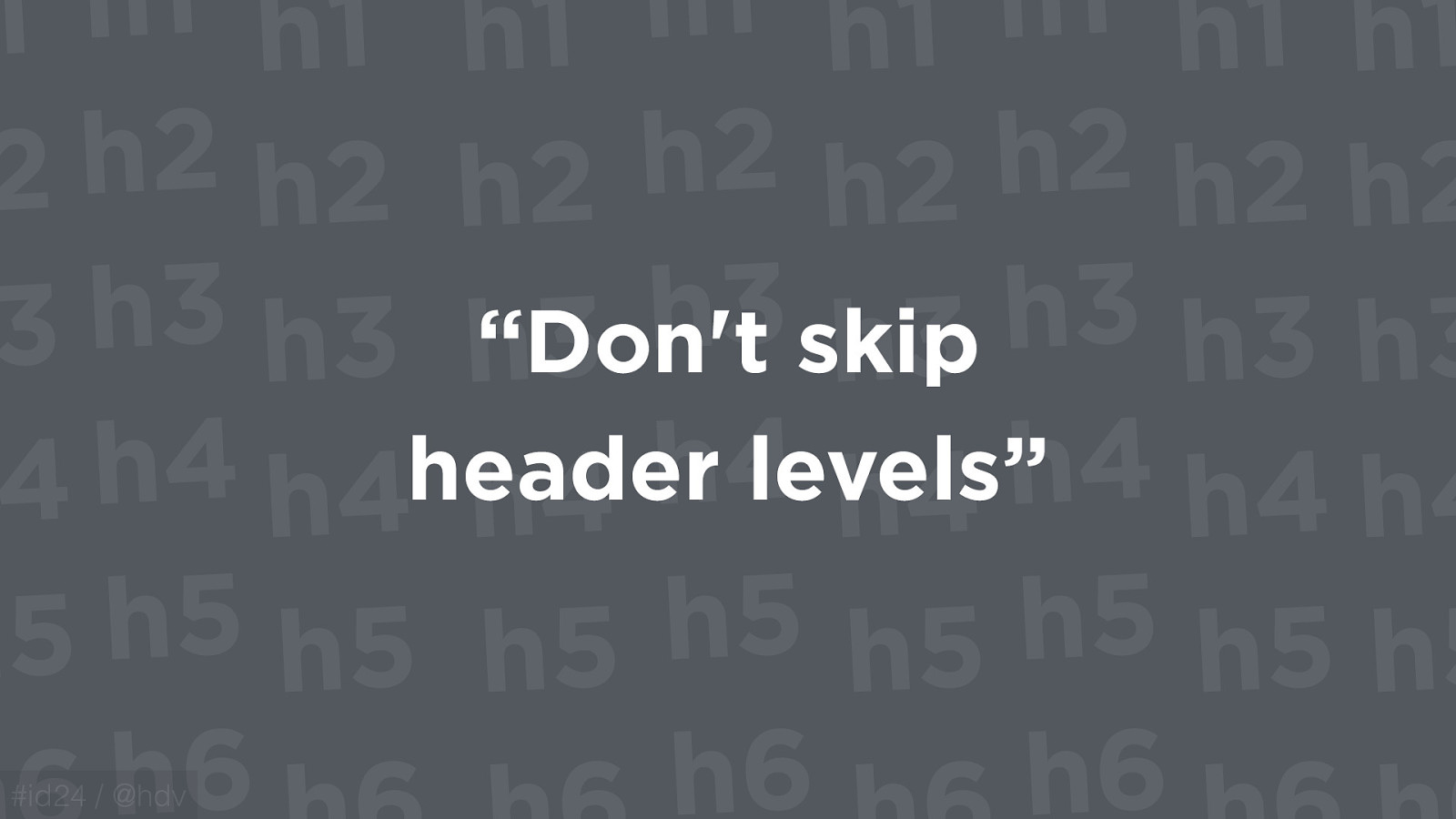

Accessibility rules can often be a theoretical. Take for example ‘Don't skip heading levels’. A great rule that accessibility experts tell teams. But just the rule is not enough, in order to get this right, it is about giving thought to circumstances. Maybe your organisation has just bought a new CMS with a very inconsistent WYSIWYG editor.

Slide 16

Vasilis, who spoke earlier, tweets this every month. Not sure if he still does, he used to anyway. “Here's your monthly reminder that your visitors are not statistics but actual people”, in which he links to the Alphabet of Accessibility Issues.

Slide 17

It explains 26 different reasons why people need your site to be accessible. If this shows anything, it is that there are lots of circumstances to take into account.

Slide 18

Aristotle saw moral behavior as a skill, we could, look at our accessibility work as the skill of trying to find the right solution.

Slide 19

The second philosopher I want to look at with you all today is Immanuel Kant. Famous for his work in metaphysics and aesthetics, but also in moral philosophy.

Slide 20

Important for understanding him, and this goes for all of the enlightment philosophers, is that he saw people as rational beings. We were born with brains, so we should use them to think things through. He also assumed people did.

Slide 21

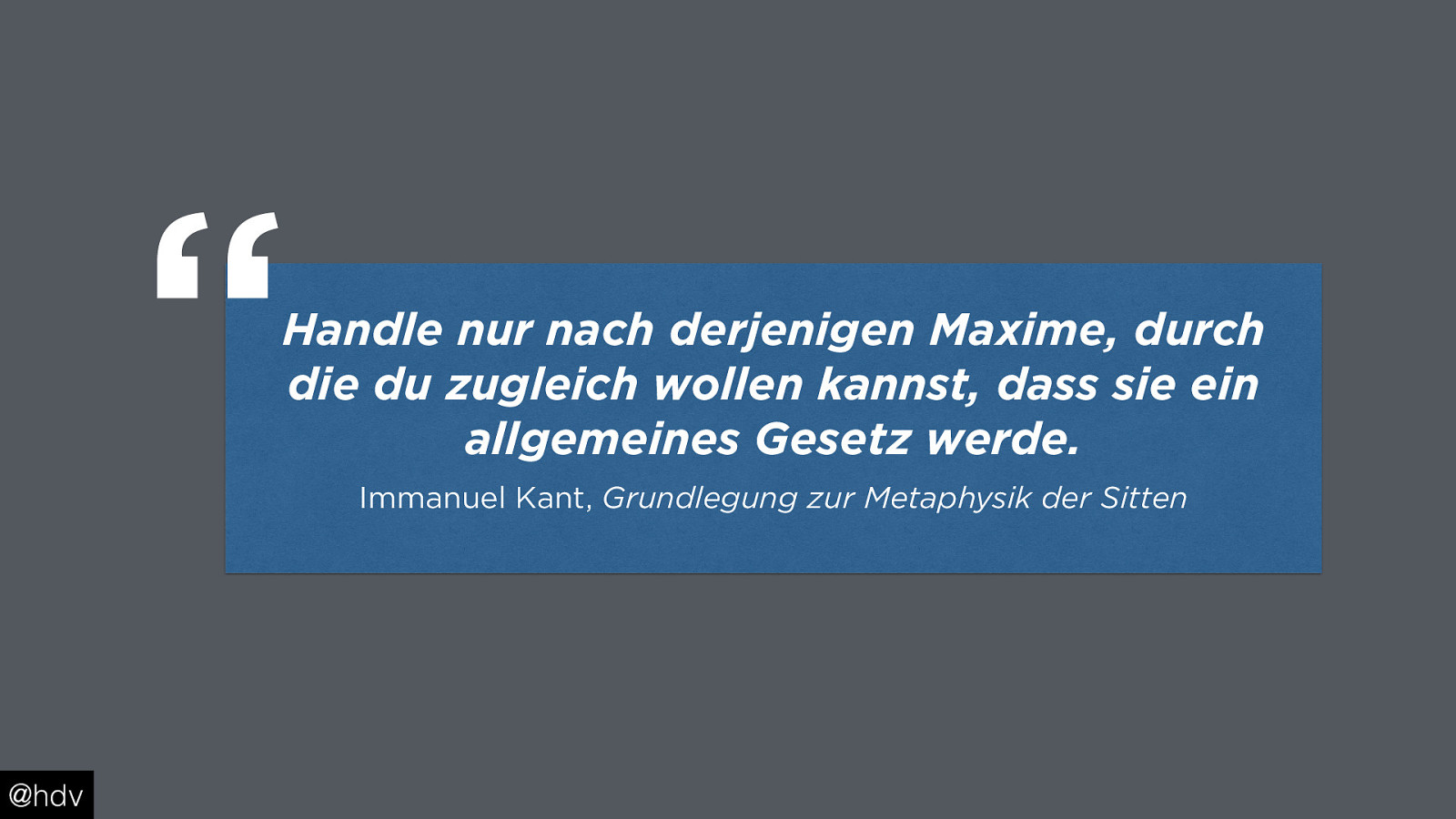

One formulations of his ethics is the categorical imperative, or “Kategorischer Imperativ”.

Slide 22

It says that we should act only by those rules of which we can at the same time want that they are a universal rule. My slide displays the quote in its original language, it will be up with captions, I won't read it out:

Handle nur nach derjenigen Maxime, durch die du zugleich wollen kannst, dass sie ein allgemeines Gesetz werde.

Slide 23

For me, it was the first and last time I ever read the word “maxim”, which means rule.

To break it up, basically this is the process: you make a rule, and then you wonder whether you could accept it if that rule would be applied to everyone, always, everywhere.

Slide 24

Kant also had this distinction between morality and prudence, he found it important that we act out of morality, not prudence. If a baker chooses not to add poison to the bread he bakes, he should do that because he believes it would be immoral to do so, not because he is afraid of losing income if his clients die. In accessibility, we could say, we want our sites to be accessible, because that's what we're supposed to do, not because the law requires it or because it would cost us customers, Kant would not see that as moral. In our work though, those can be great and effective reasons to convince co-workers or management. So I'd argue we can be pragmatic and don't need this distinction on the web,

Slide 25

The last philosopher we'll look at is Jeremy Bentham, who was a utilitarianist. We saw that for Kant it is a lot about actions themselves and our reasons for them. For utilitarianists, it is all about the outcome of our actions.

Slide 26

Bentham formulated the Greatest Happiness Principle. Basically, actions are good if they increase total happiness in the world.

Slide 27

So there's happiness, and for any action, we can establish if they improve the world's total happiness.

Slide 28

What an increase looks like is a bit controversial amongst utilitarianists, by the way, but that's ok for our current purposes.

Slide 29

So, on the web, we should try and only make changes that increase happiness.

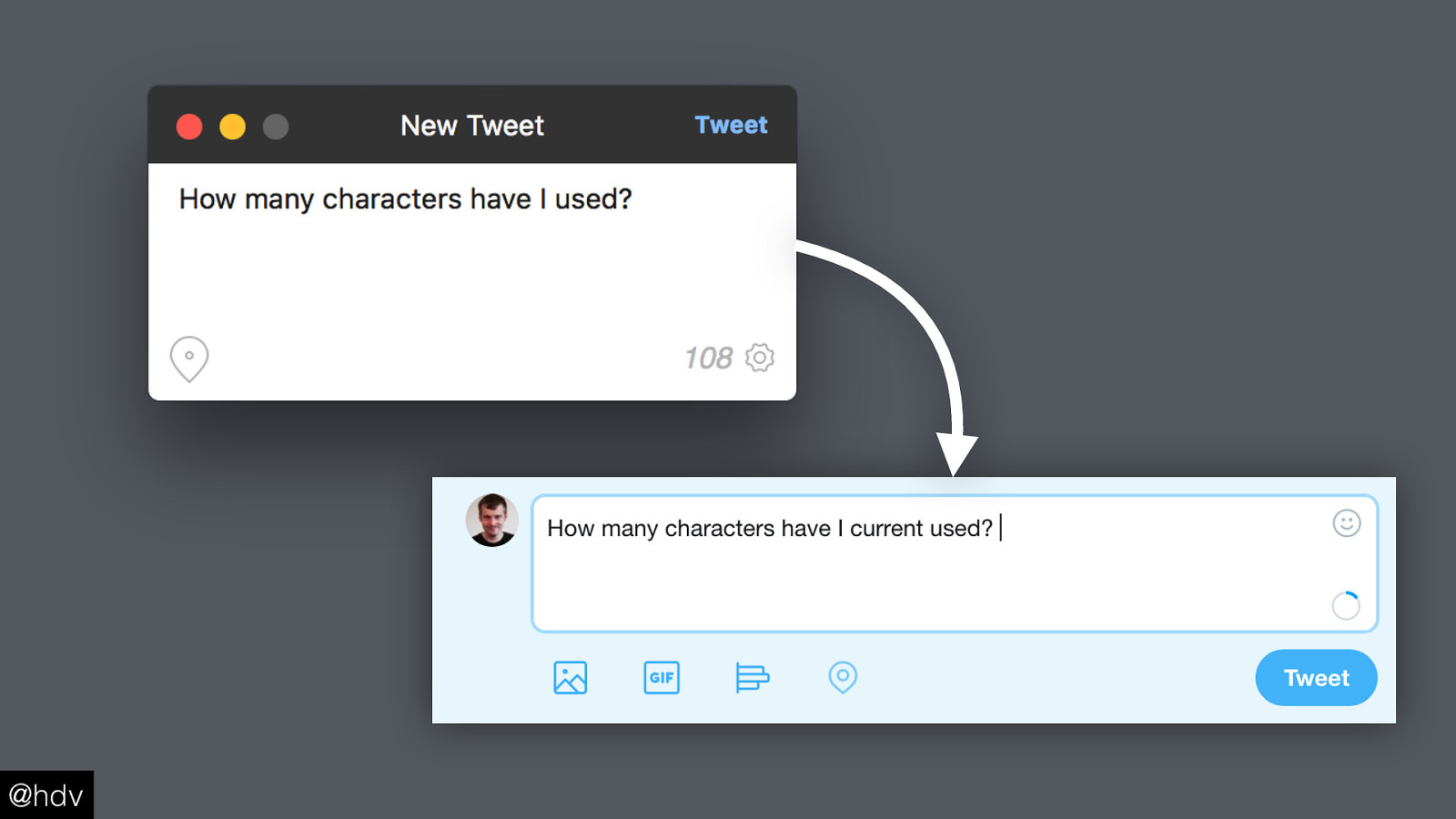

Slide 30

Twitter, for example, made a change where they removed the character count from their Compose screen and replaced it by some sort of pie chart. Did it make people happy?

Slide 31

Nah, not really. Alan Cooper called the new design ‘abysmally stupid and bad design’.

Slide 32

Someone going by the name Harvest Pixie Dream Witch, asked ‘what the heck is this gradually filling circle of tweet character doom?’

Slide 33

People even created browser plugins to take matters into their own hands.

Slide 34

So, the action did not really increase the world's total happiness, one might say. How can we apply the greatest happiness principle to web accessibility?

Slide 35

Well, we could ask: does my action increase the website's total accessibility?

Slide 36

Something I live by, is something Léonie Watson said: it doesn't have to be perfect, it just has to be a little bit better than yesterday. This works really well with the greatest happiness principle, you can make small improvements and each one can make the world a little bit better.

Slide 37

So, we've looked at virtue ethics, that is about character traits, we looked at Kant, who emphasises we should be rational and consider the motives for our actions, and utilitarianists, for whom the outcome of actions is more important than the actions themselves.

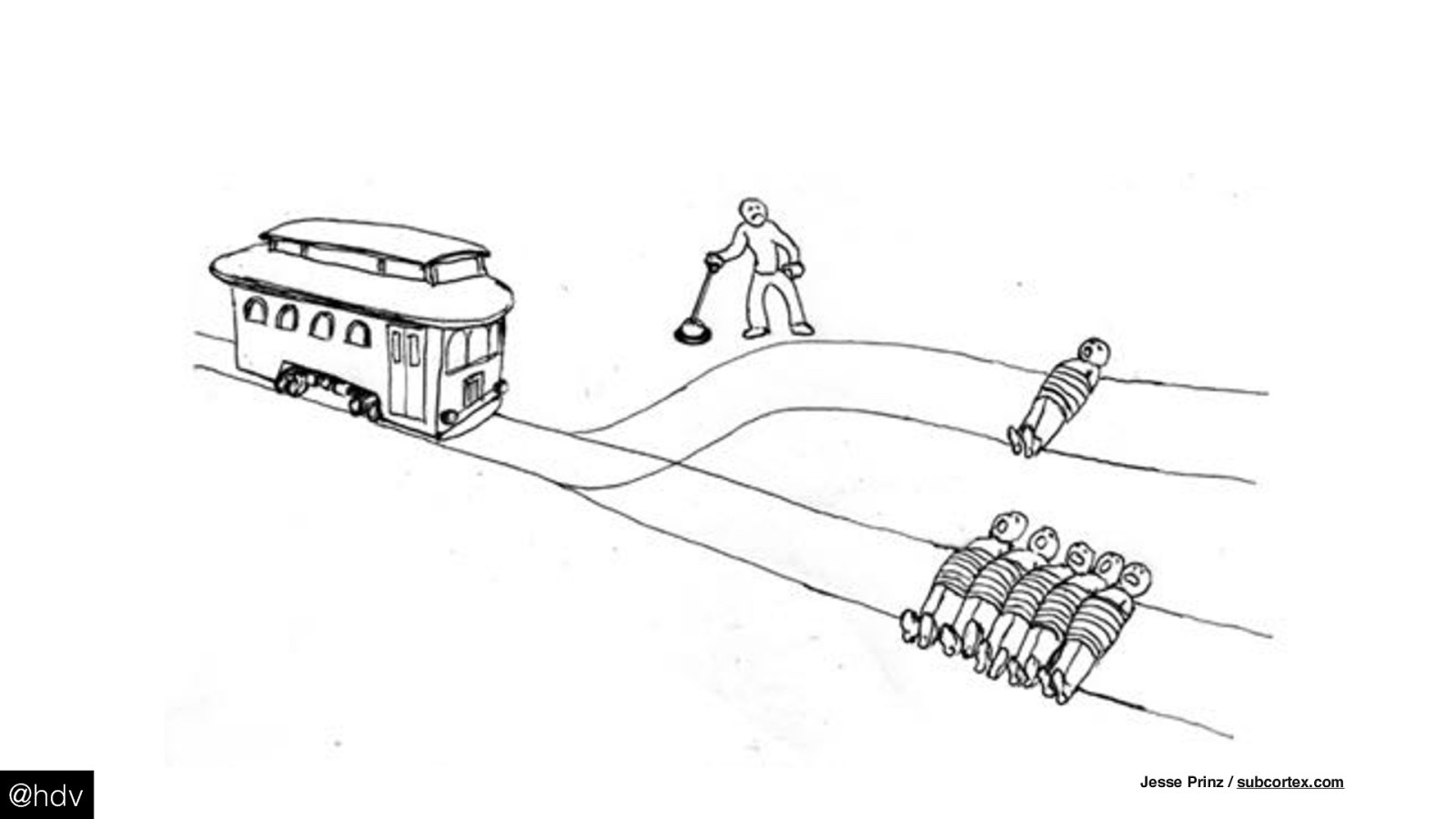

Slide 38

Let's look at some thought experiments, we'll start with the Trolley Problem, originally by Philippa Foot.

Slide 39

The idea is: a trolley is driving on a railway track, but right ahead of it is 5 people, who have been tied to the track by an evil madmen. All five would get killed if the driver were to drive ahead. There is one way the driver can save the situation, which is by pulling the lever and diverting the train into a second track. This track also has a person tied to it, same evil mad man. The question is, should we divert the train?

Slide 40

Harvard's rockstar philosopher Michael Sandel asked his students and a majority said yes, totally, we should divert the train.

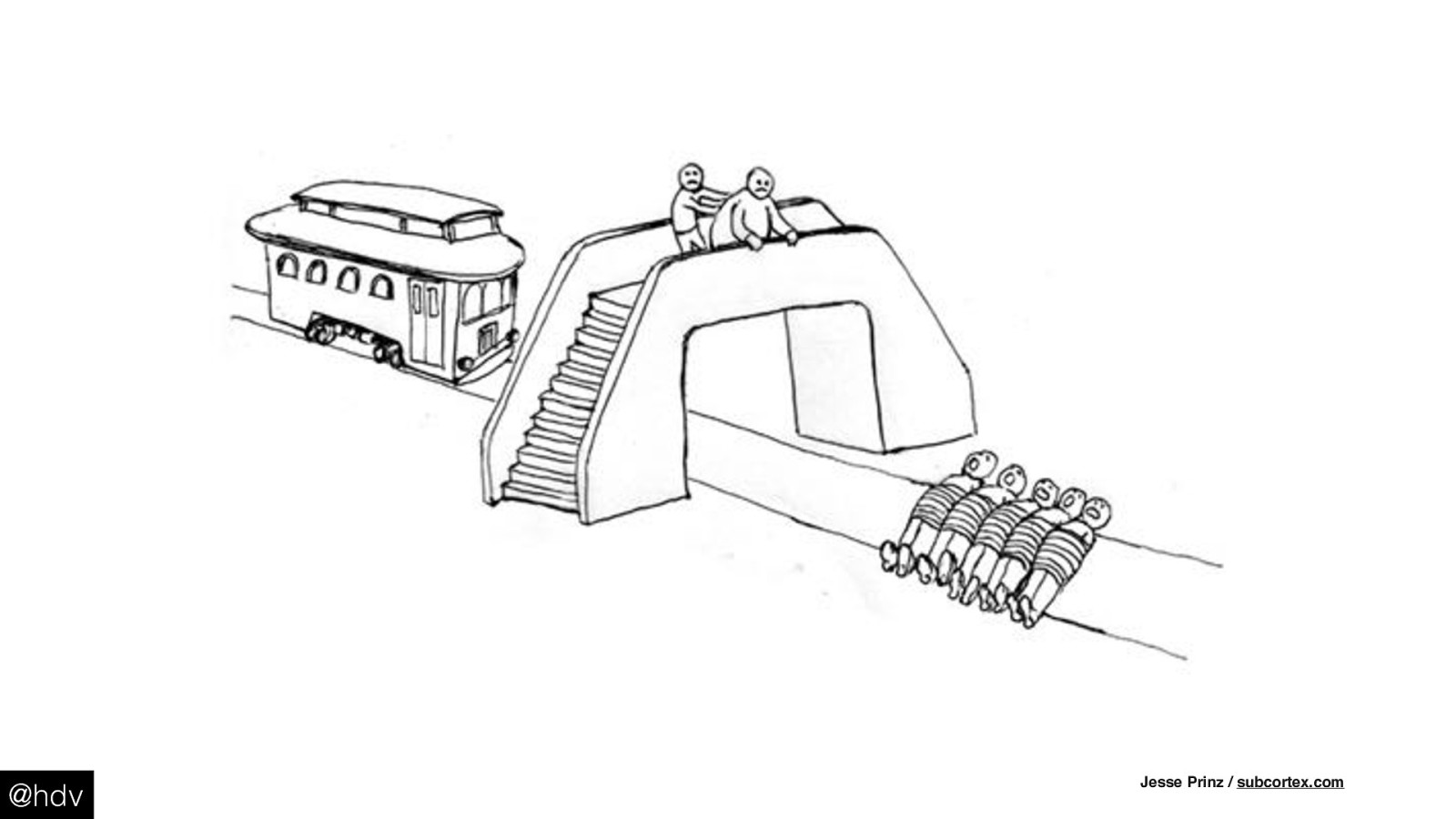

Slide 41

The dilemma gets more complicated in this second example, where there is a bridge over the track. The same five people are tied to the track. On the bridge, there is a man and if we were to push the man in front of the train, it would be put to a stop and save the five people. But yea, we would have been actively involved with killing.

Slide 42

If I had to summarise: this is about making the right choices. We do this all the time on the web.

Slide 43

Let's say we're building a footer and the designer has chosen some beautiful shades of grey, however they don't match the contrast requirements.

Slide 44

This is a choice between. let's make it black and white, lots of subtle shads of grey, or lots of contrast.

Slide 45

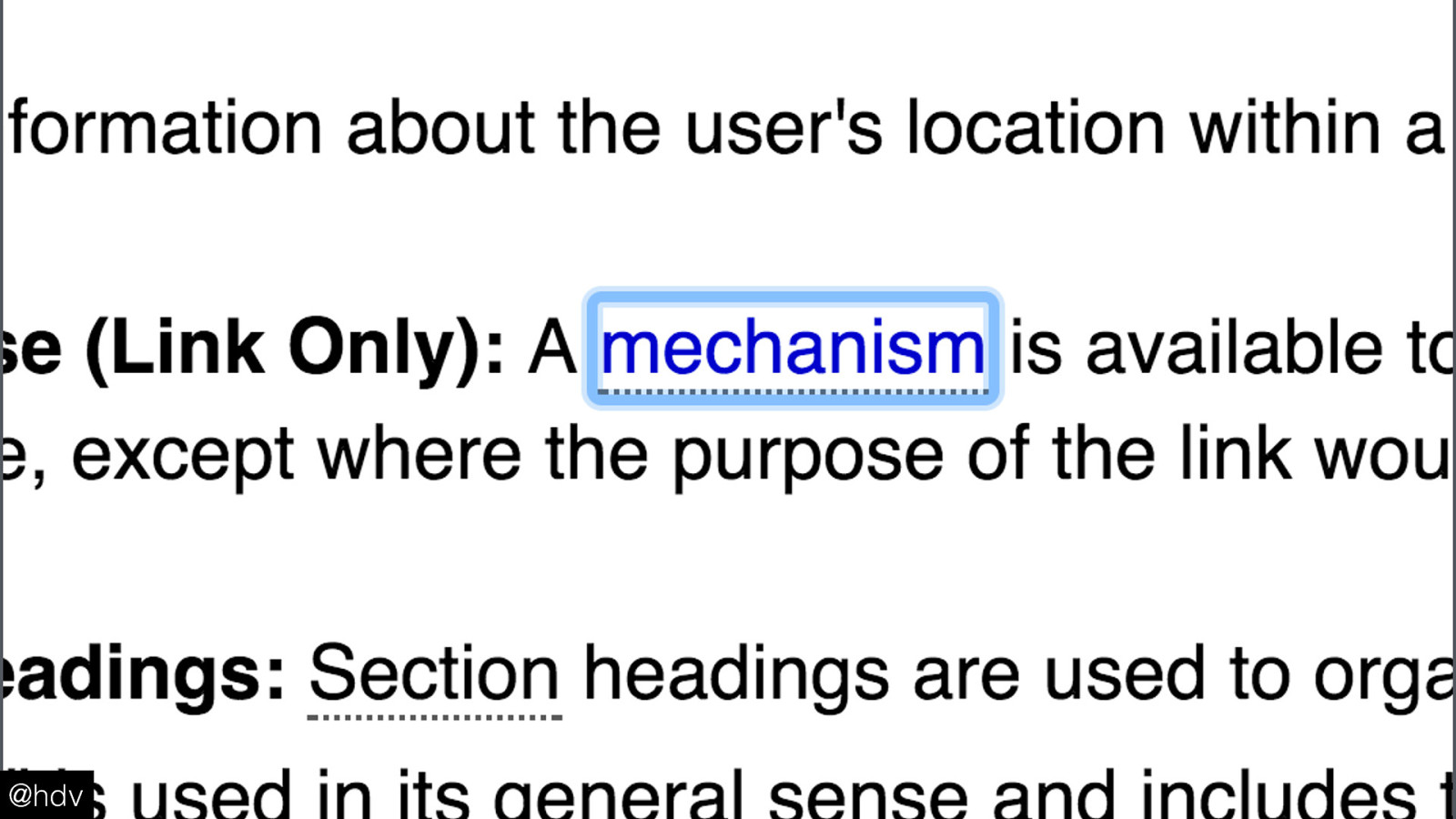

What about focus styles? Maybe you're working with someone who doesn't like the look of them.

Slide 46

That makes this a choice between setting styles to outline none or designing a prettier focus indicator.

Slide 47

I believe that as digital teams, we have a lever to pull, and the good thing is, we don't even need to kill anyone.

Slide 48

Let's look at the second example, John Rawls' veil of ignorance.

Slide 49

Rawls describes in his political philosophy the concept of a veil of ignorance. The idea of it is that a group of people is asked to make the moral rules for a society, but before they get a chance, they are first stripped from their position in society. In other words, they don't know if they will be Uber's CEO or an Uber driver, or 'partner' or whatever Uber names them.

Slide 50

Or think of a group of people who can decide on immigration rules and laws related to borders, but first, their passports are taken away, and afterwards they are randomly distributed. This is called the Original Position.

Slide 51

The idea of it is that in the original position, you are stripped from privilege and in that position, you will come up with the fairest possible rules.

Slide 52

We can do this on the web! We can consider new features from the original position.

Slide 53

So when we build a new feature, let's forget about our own retina screen, where we were born and how fast our WiFi is.

Slide 54

The last example I want to talk about is the Prisoner's Dilemma.

Slide 55

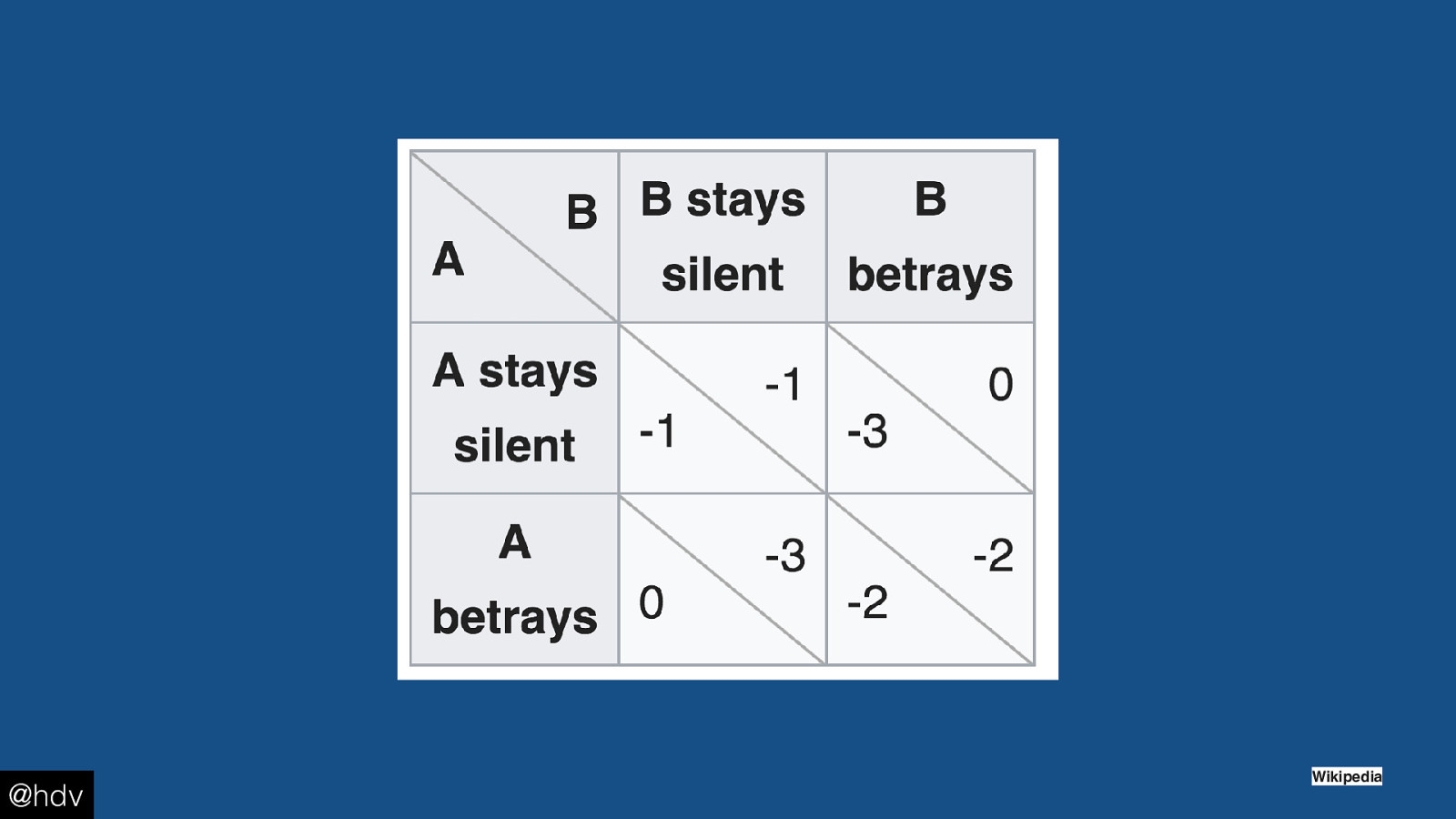

The idea here is that 2 members of the same gang are arrested, but the prosecutor doesn't really have enough evidence to put them away for more than a year. However if one of them betrays the other and shares some vital information, the prosecutor could put that other person away for 3 years and would be willing to let the first person walk out for free. If they both betray, they'd get out after 2 years.

Slide 56

So this is it in a table form: if they don't betray each other, they only need to go into prison for 1 year, if one betrays the other they walk out free but the other serves 3 years, and if they betray each other they both go into prison for 2 years.

Slide 57

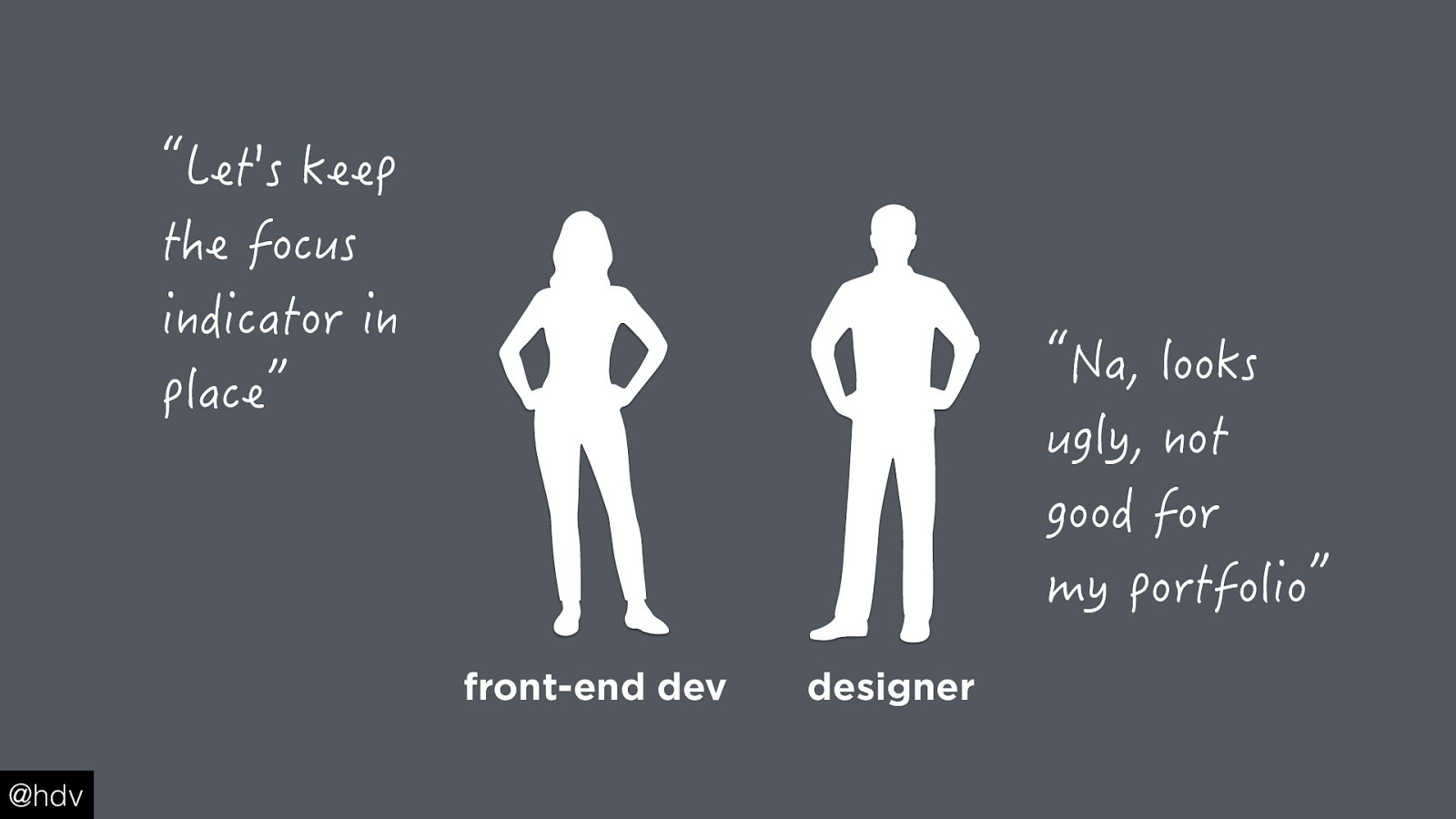

This is all about conflicting interests. And yes, we have those when working in digital taems!

Slide 58

Let's imagine a front-end developer who says they want to keep a focus indicator in place, talking to a designer who says they don't want to do that as it would not look good on their portfolio?

Slide 59

Or an SEO expert arguing to have all the things H1, and an accessibility expert going 'noo, we need a sensible heading structure'.

Slide 60

Or perhaps a frnot-end dev who asks for extra time to make a carousel more inclusive, with the CEO saying no they want to spend extra bufget on a TV ad instead.

Slide 61

This is about lining up interests to get more people care about accessibility.

Slide 62

In other words, we need to make the business case, learn to speak the language of the business people and then convince them.

Slide 63

This may sound boring but it is not, as Alice Bartlett showed in her Fronteers talk ‘What is the business case for accessibility?’ https://vimeo.com/145138872

Slide 64

The great news is that in the real world, we are not behind bars and we can actually talk to each other.

Slide 65

So, we looked at the Trolley Problem, at the Veil of Ignorance and at the Prisoner's Dilemma.

Slide 66

I'm going to summarise them in very few words: this is about making good choices, thinking beyond our own privilege and lining up interests.

Slide 67

Thanks very much for listening, these slides are on notist, and if anyone has questions, email me or tweet @hdv.