Thanks all for joining this session, in which I’ll try and combine two things: philosophy and web accessibility.

Slide 1

Slide 2

You may be wondering why, and the reason is simple… I studied philosophy in uni, but never really used it in my daily work… this seemed like an excellent opportunity to be doing exactly that. Philosophy and ethics aren’t usually taught in digital design or computer science programs.

Slide 3

My name is Hidde de Vries, and my current job title is Web Developer and Accessibility Specialist. I’m part of a European Commission funded project at the W3C.

Slide 4

The W3C, or World Wide Web Consortium, is an organisation that creates standards for the web. I specifically work in a team called WAI, or Web Accessibility Initiative, which has as its mission to ensure that the web is accessible to people with disabilities.

Slide 5

One way we do that is through creating standards for accessibility. The one many here will be familiar with is called WCAG, or Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. It is embraced by governments around the world as the document that specifies what accessibility of websites looks like.

Slide 6

There’s also others… ATAG is a standard for accessibility of tools that create websites, like Content Management Systems and e-learning. If you work with CMSes, please do come to talk to me later.

Slide 7

There’s UAAG that is specifically for browsers.

Slide 8

And then there’s ARIA, a standard that adds a layer onto HTML for specifying accessibility specific meta information.

Slide 9

These standards are fairly technical documents, and they have to be, for all sorts of reasons, which is why at WAI, we also create lots of guidance around these standards. Because I’m sure it can benefit many of you and your colleagues, I would like to bring to your attention the WAI website, which is on w3.org/WAI, it’s a great resource for anything related to accessibility… creating web products, but also planning, testing, advocating and more. So, have a look at this.

Slide 10

I did promise you that this talk would include philosophy. What you see here, is a work from the Renaissance painter Raphael, called “The School of Athens”. Many associate philosophy as something from ancient Greek times… old bearded men, talking about life. And, yes, we’ll talk about some of that. But philosophy is also great at considering reasons for doing things. We’ll do some of that today, too. Because one of the things you’ll note if you work in accessibility that, probably as in many other fields, you’ll have to explain to others why it is important.

Slide 11

There are several good arguments for making accessible websites.

Slide 12

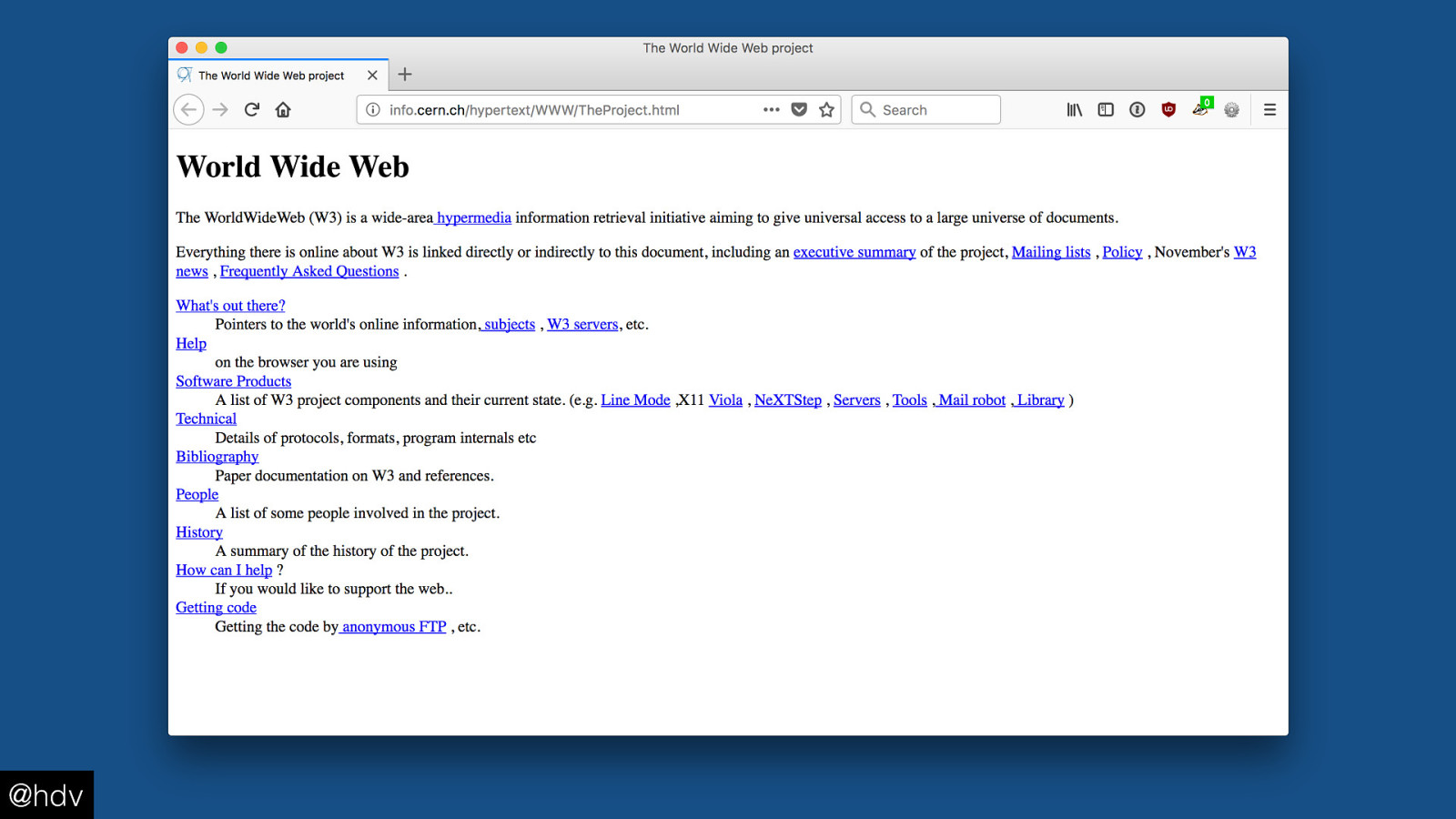

One that has always appealed to me, because I’ve worked as a developer a lot, is the technical argument. One aspect of that is… accessible code is easier to maintain, because it has more structure. Another is the idea that the web is accessible by default.

Slide 13

I mean, the first website, which was just a page titled “World Wide Web”, would qualify as quite an accessible page, because it is mostly structured text. It has lots of contrast, it won’t break when you zoom in, links are clearly identified…

Slide 14

So that’s the technical argument.

Slide 15

There’s also plenty of legal reasons to be making sites accessible. The law says in many areas of the world that websites ought to be accessible, see for example the European Web Accessibility Directive.

Slide 16

There’s business arguments to make too, and we’ll talk about that in a little more detail later… but the gist is, if your business is open to more people, you can earn more money.

Slide 17

And then there’s the moral argument for accessibility, which we’ll focus on today.

Slide 18

So what’s ethics? Or… better… what kinds of questions does it answer for us? It is questions like how should we live…

Slide 19

…what are the right things to do…

Slide 20

…and how we want our world to be shaped. Pretty fundamental questions, I think, but not necessarily easy to answer. Now it may seem that these are questions that are mostly about the world and not about the IT sector. Well, I’d say they are essential questions in the IT sector. I’ll give a couple of examples. They are randomly selected, and all happen to be about products from Silicon Valley.

Slide 21

Name Facebook… lots of ethical questions apply to them. To name just one… free speech! Is it okay for people to lie on Facebook, what about in ads and what about political ads? Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg recently shared his thoughts about these questions, which are very much ethical in nature.

Slide 22

Or Netflix… on a whole different level, they have a role in what we do, because they influence what kind of culture we consume, with their sophisticated recommendation algorithms.

Slide 23

AirBnb has questions on a different level too… their platform impacts what our world looks like and influences things like how the housing market works in certain cities. Lots of ethical dimensions to that.

Slide 24

So, for now, I’ll reduce it to these three questions… let’s say this is what ethics is about.

Slide 25

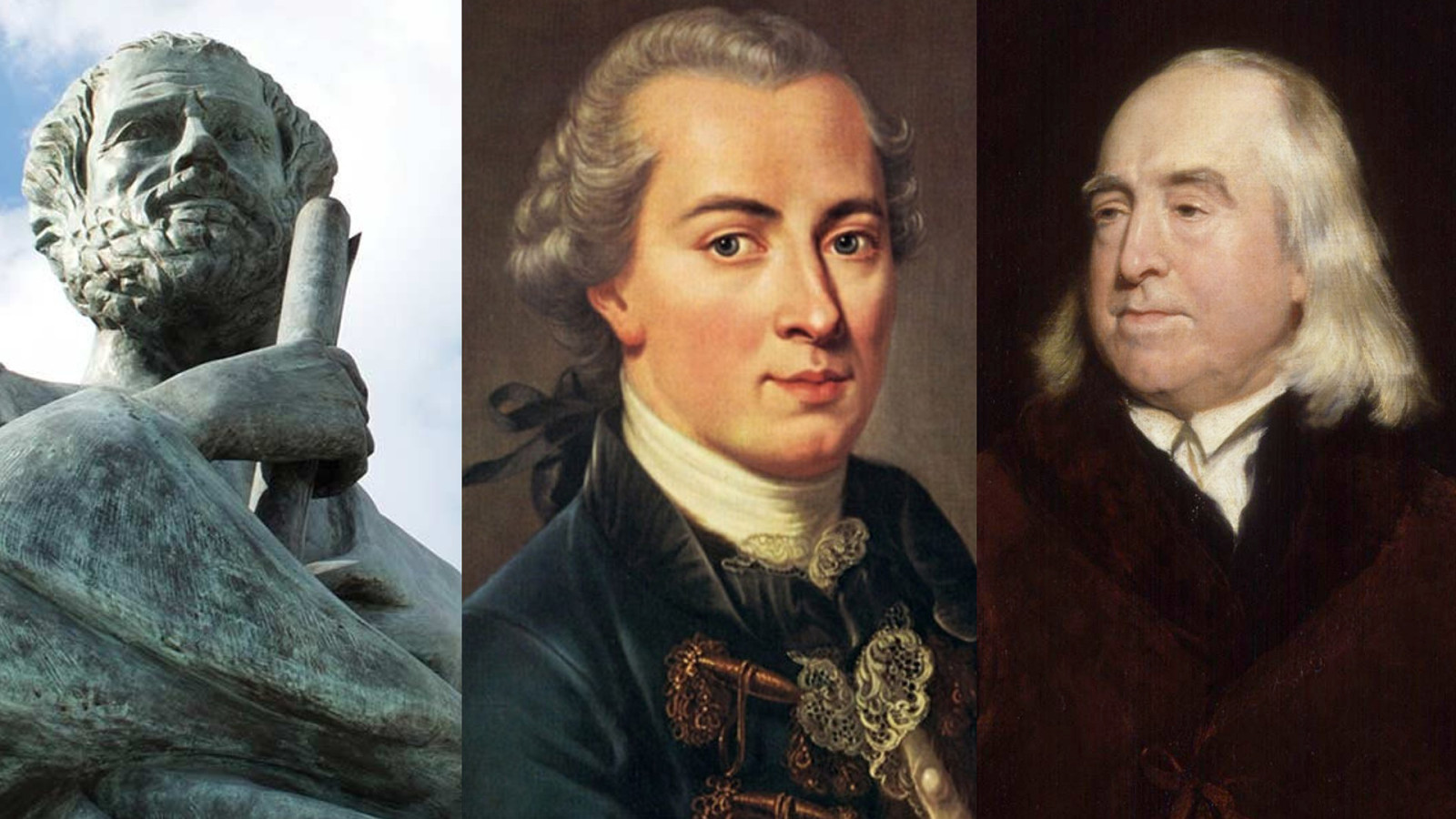

Within ethics, it is common to group ethical theories in these three groups: virtue ethics, duty ethics and utilitarianism.

Slide 26

Let’s get started with a philosopher who lived thousands of years ago… this is Aristotle, a statue of him. Before him, philosophers were mostly concerned with nature, being almost what we call geologists today. Aristotle is the very first philosopher to write a work dedicated to ethics.

Slide 27

One of the things that is interesting about Aristotelean ethics is that it isn’t about learning a set of rules on how to live or what to do, it is really about improving one’s character.

Slide 28

In his theory, a number of character traits are defined, a set of different virtues (this is why it is called virtue ethics).

Slide 29

One doesn’t just become virtuous, this is a process that can take years, in which a person slowly becomes ethical over time, by improving their character traits.

Slide 30

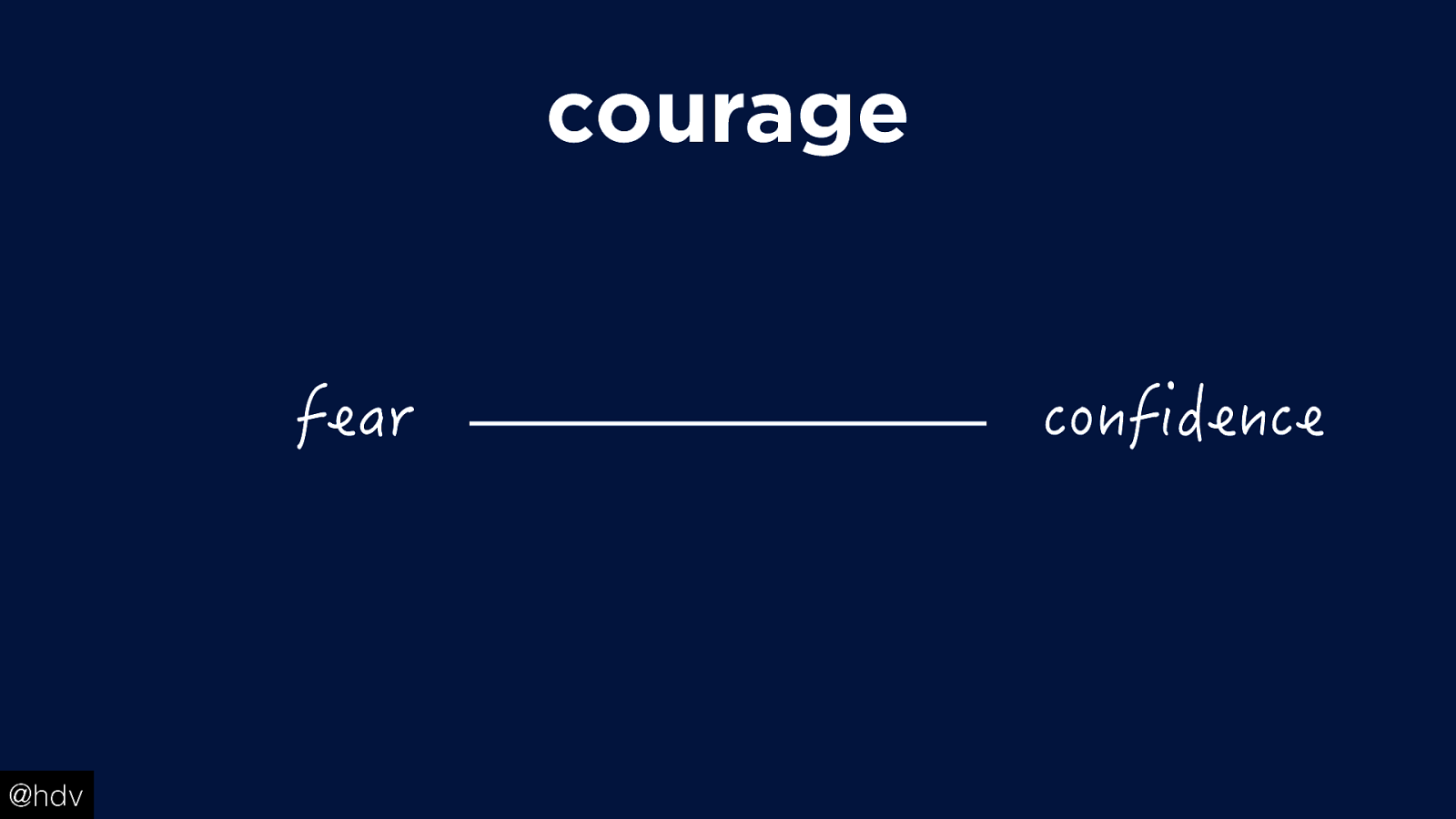

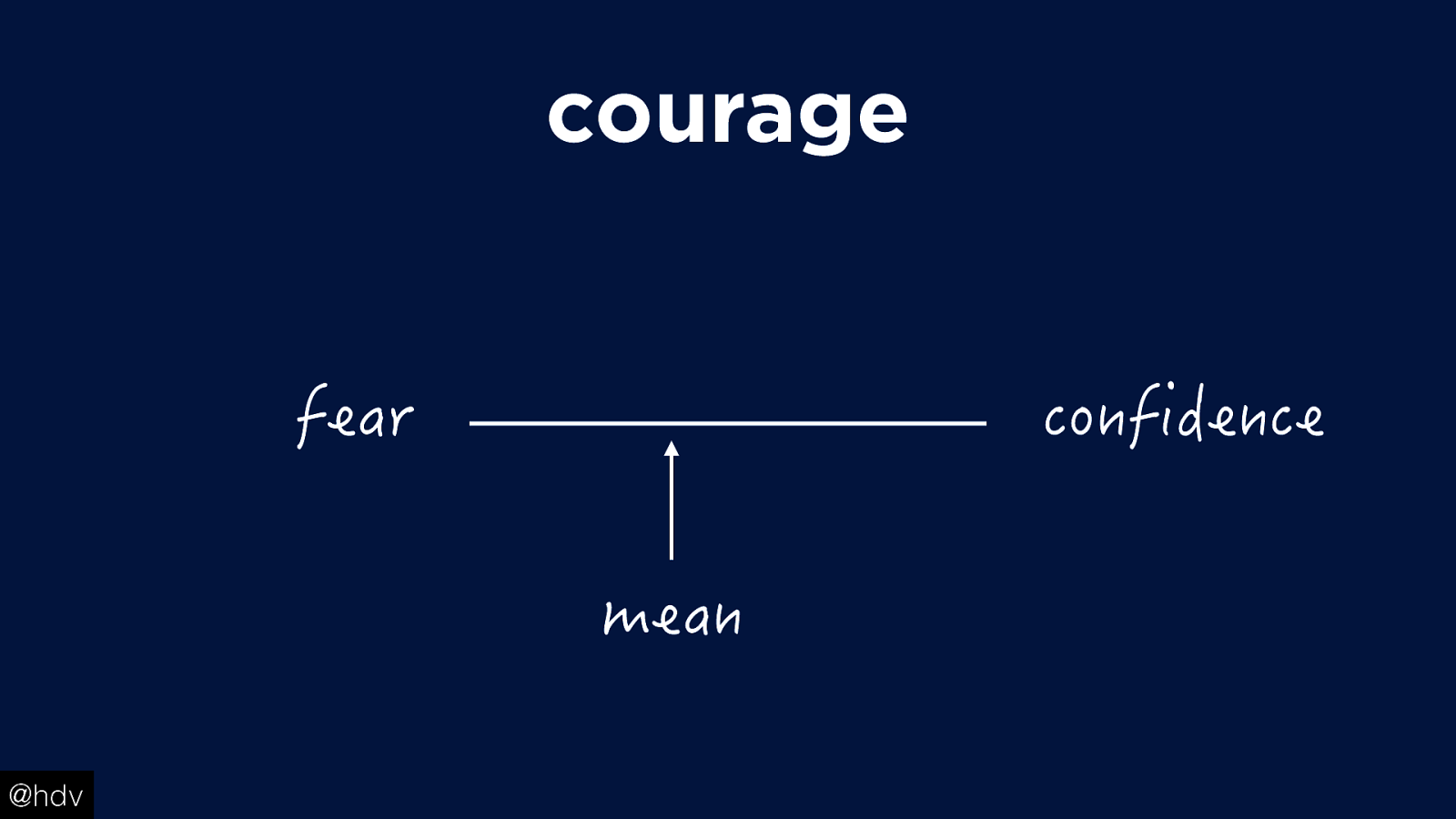

Aristotle thought of being virtuous as being somewhere between two extremes. Let’s take “courage” as an example… you don’t want to be scared of everything, that does not work. On the other hand, you also don’t want to be too confident, that also doesn’t work. Being ethical means being somewhere between those two extremes, and it takes time to learn where to be.

Slide 31

It is about finding the right “mean”.

Slide 32

Another interesting aspect of how Aristotle thought about these things, is that he considered circumstances to be essential in learning to develop character traits.

Slide 33

Giving thought to circumstances helps find the best mean between two extreme sides of a specific virtue. Circumstances also play an important part in doing accessibility.

Slide 34

There’s many rules we learn as accessibility experts, like “Don’t skip header levels”…

Slide 35

…and “use semantic markup”. These are definitely important as a baseline, but when doing the actual work to get these rules applied in a web product, there are often circumstances that come into play. Maybe the CMS simply can’t do the markup that is required, maybe a designer wants to have a visual lay-out that doesn’t take header levels into account. To be someone who gets accessibility done in an organisation, is to be someone who can navigate circumstances.

But it’s not just organisational circumstances that are important in accessibility. This conference is about putting users in the centre of everything. They are our circumstances.

Slide 36

Vasilis van Gemert, a teacher at the University of Applied Sciences, tweets this every month: “here’s your monthly reminder that your visitors are not statistics but actual people”. The tweet links to a blogpost…

Slide 37

…that is called “An Alphabet of Accessibility Issues”. It lists 26 different access needs that people may have, and I think it is a brilliant illustration of the fact that the people we make websites accessibility for, is an extremely varied bunch. There are a lot of different people that benefit from accessibility improvements.

Slide 38

So, Aristotle positioned ethics as developing one’s character and taking into account circumstances, I think what we need to do as accessibility experts, is developing one’s knowledge alongside being great at understanding and dealing with circumstances, both in our organisations and among our users.

Slide 39

Let’s now move onto the next person, the Enlightment philosopher Immannuel Kant. He is wlel known for his work in the philosophy of art and metaphysics, but also wrote a comprehensive account of ethics.

Slide 40

Central to Kant’s ethics, and in the thinking of enlightment philosophers in general, is that he regards people as rational beings, as opposed to, say, animals or robots. We have a mind that we can use to consider thoughtfully what we ought to do.

Slide 41

In his theory, Kant defines the “categorial imperative”. Let’s break the two parts of that phrase down.

Categorical in this sense means something like universal, applying to all of us. Imperative means this is an obligation. Point is: this is not subjective, as he claims ethical theories before his were.

Slide 42

This is one of his formulations of the categorial imperative:

Act only acording to that maxim by which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law

For many philosophy students, this is the first and last time they see the word ‘maxim’ used. It can be seen as ‘rule’.

So only do stuff according to rules that you’d want to apply to everyone. This is about sticking to principles. If your principle is ‘don’t lie’, you should never lie, including when a lie might be beneficial to yourself or your friends.

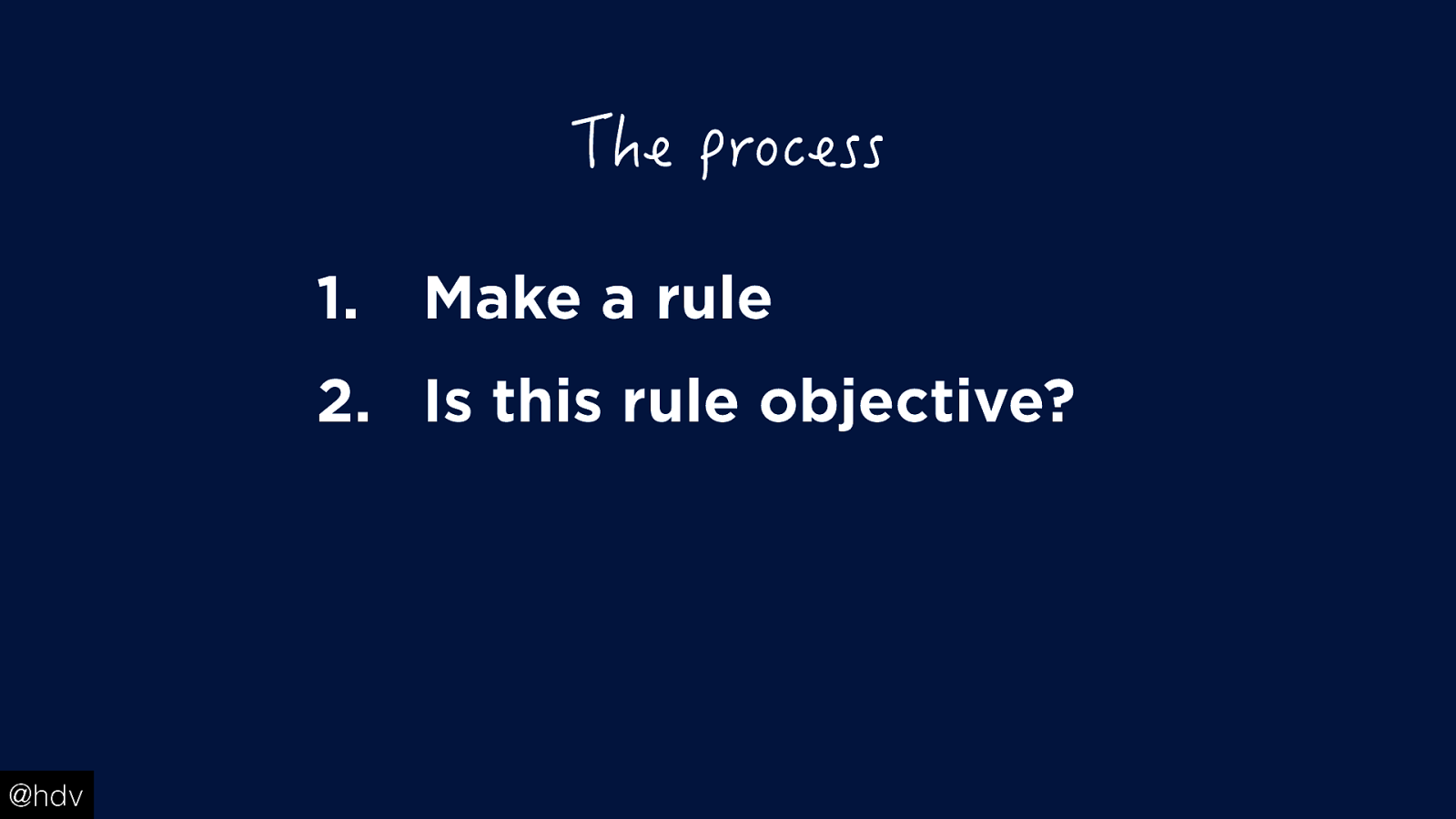

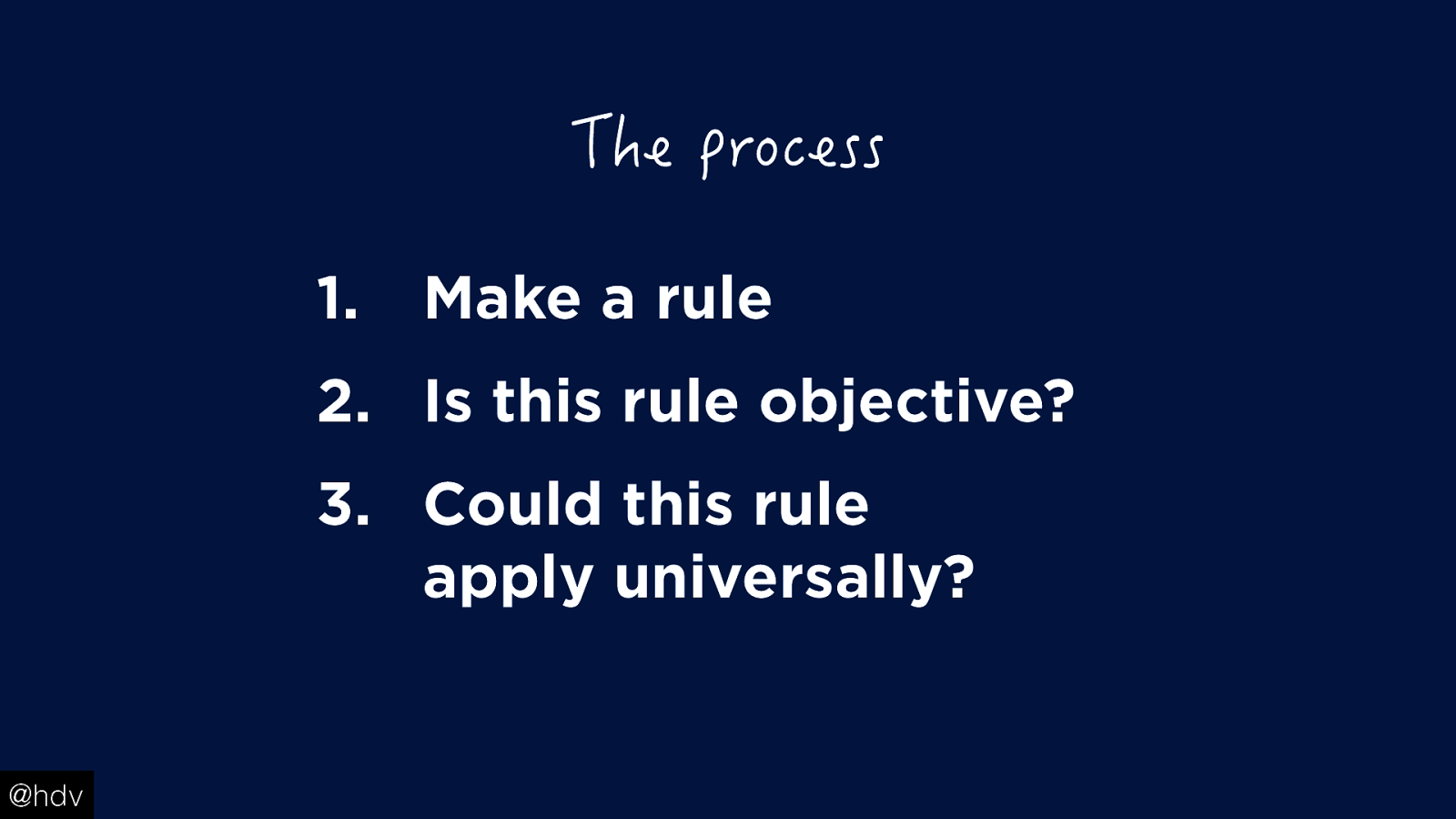

Slide 43

So this is the process. Make a rule, for example “Don’t steal”.

Slide 44

Slide 45

Then the second question, is this objective, as in… not subjective?

Slide 46

Thirdly, would it make sense to apply this rule always, to everyone, universally, and is it a necessary duty? That seems to work for “Don’t steal”, the world works much better if that is adopted as a rule.

Slide 47

The difference between morality and prudence is important for Kant, too.

In Kants ethics, acting out of self interest can’t be moral, you should always act out of principles. If you’re a baker and you don’t add poison into your bread because you don’t want to lose clients, that is a prudential motivation. It has no meaning on the scale of morality. A moral reason would be something like “Don’t poison your clients”.

Applied to accessibility, for Kant, we would improve the accessibility of our sites because we think that’s how sites should be, this is how the web was intended. If you would do it only because it makes your company more profit, Kant wouldn’t classify that as moral.

Slide 48

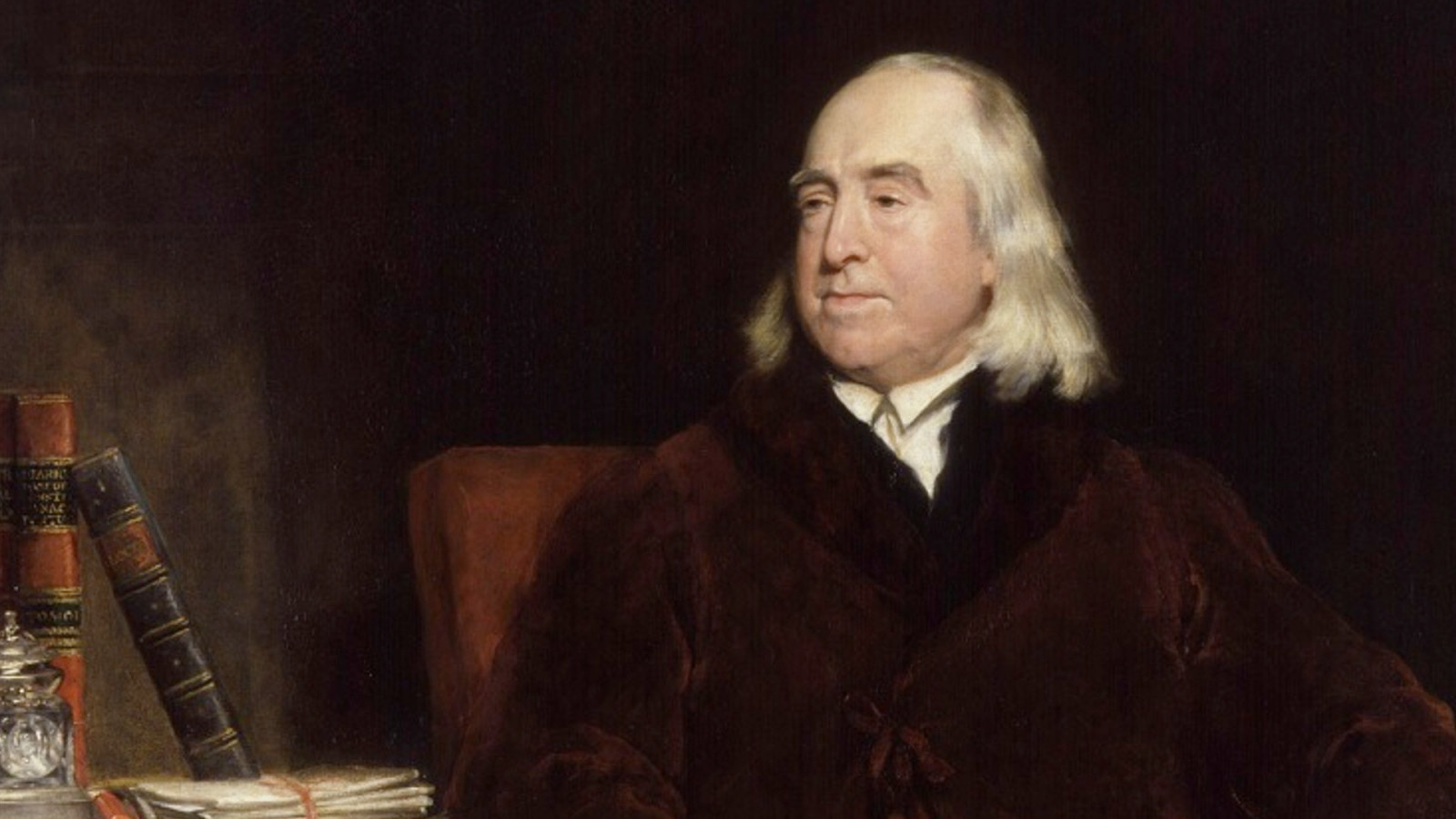

Most ethicists today will think of themselves as Kantian or utilitarian. So, making another huge jump in history, let’s look at what that means. This is Jeremy Benthem.

Utilitarianists decide what the right thing is by looking at outcomes, or the contribution of our actions on the world’s total happiness. The best way to act is the way that increases happiness the most.

Slide 49

Jeremy Bentham came up with what he called the greatest happiness principle. According to it, actions are right if they promote happiness, wrong if they promote the reverse of happiness.

Slide 50

So the question to ask is: does my action increase the world’s total happiness? It’s like regarding the world’s happiness as a basket and thinking of your actions as potential things you could put in there.

Slide 51

The question that many utilitarians disagree about is what an increase in happiness means. Is it your own happiness, your company’s happiness? Well for us, it is probably user happiness.

Slide 52

The lesson for web accessibility that we can learn here is: make changes that increase happiness, avoid those that don’t.

Slide 53

Maybe we can look at this as: does my action increase the website’s total accessibility? And look at this in a super broad sense. In no website, accessibility is the only aspect we worry about. In this, you can replace accessibility with performance, usability, et cetera.

And thinking about it like this, we can avoid the pitfall of thinking about accessibility as an all or nothing equation.

Slide 54

As the awesome accessibility expert Léonie Watson likes to emphasise in her talks: “it doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to be a little bit better than yesterday”. Small improvements are helpful, they can increase the total amount of accessibility in this world.

Slide 55

Concluding: so that is a couple of examples of attitudes philosophers have had towards ethics, how to live and deciding how to live.

Aristotle thought of it as developing certain character traits and gaining skills as it where.

Kant thought of it as a necessary, universal thing. For him motive matters.

Bentham thought of morality in terms of how their consequences: how they contribute to the world’s happiness.

Slide 56

So having looked at some background, let us now look at some thought experiments.

Slide 57

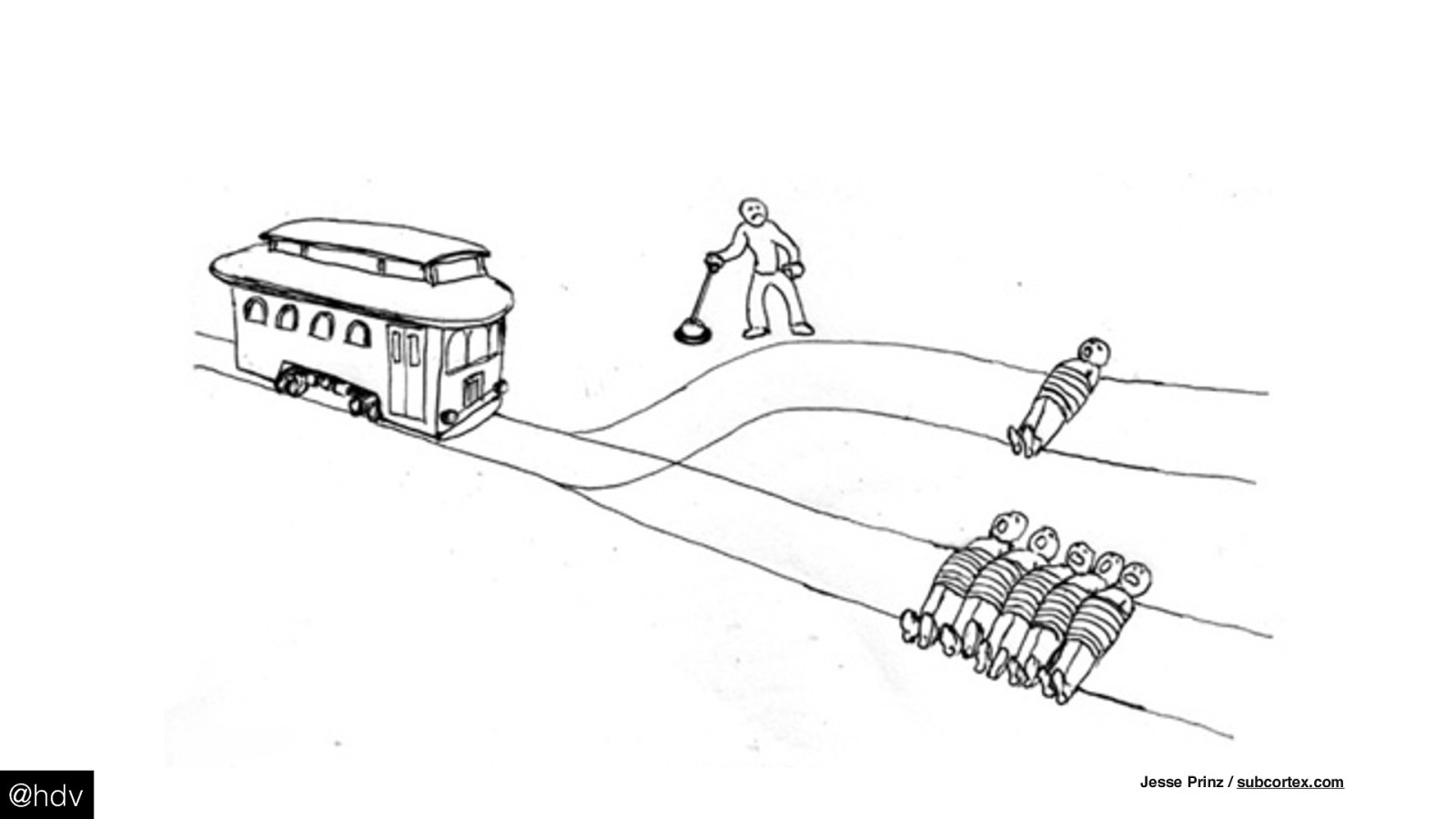

This is the example:

You are looking at a trolley and as it is moving along, you notice there are five people on the track, which the trolley would kill if moving ahead. You have the chance to divert the trolley by pulling a lever. The diverted track has one person on it, and if moving ahead, that one person would get killed. Do you divert the trolley?

If you do, you save five people, but in turn you do kill one person. It’s almost spreadsheet-based philosophy: the idea here is that killing one person is better than killing five.

Slide 58

There’s a video of the American rock star philosopher Michael Sandel who asks his students this question: what would you do? At this Harvard event, the majority of people put there hand up and voted for choosing to kill the one person, only a handful would drive ahead.

It seems that helping as many people as possible fits our moral intuitions.

Slide 59

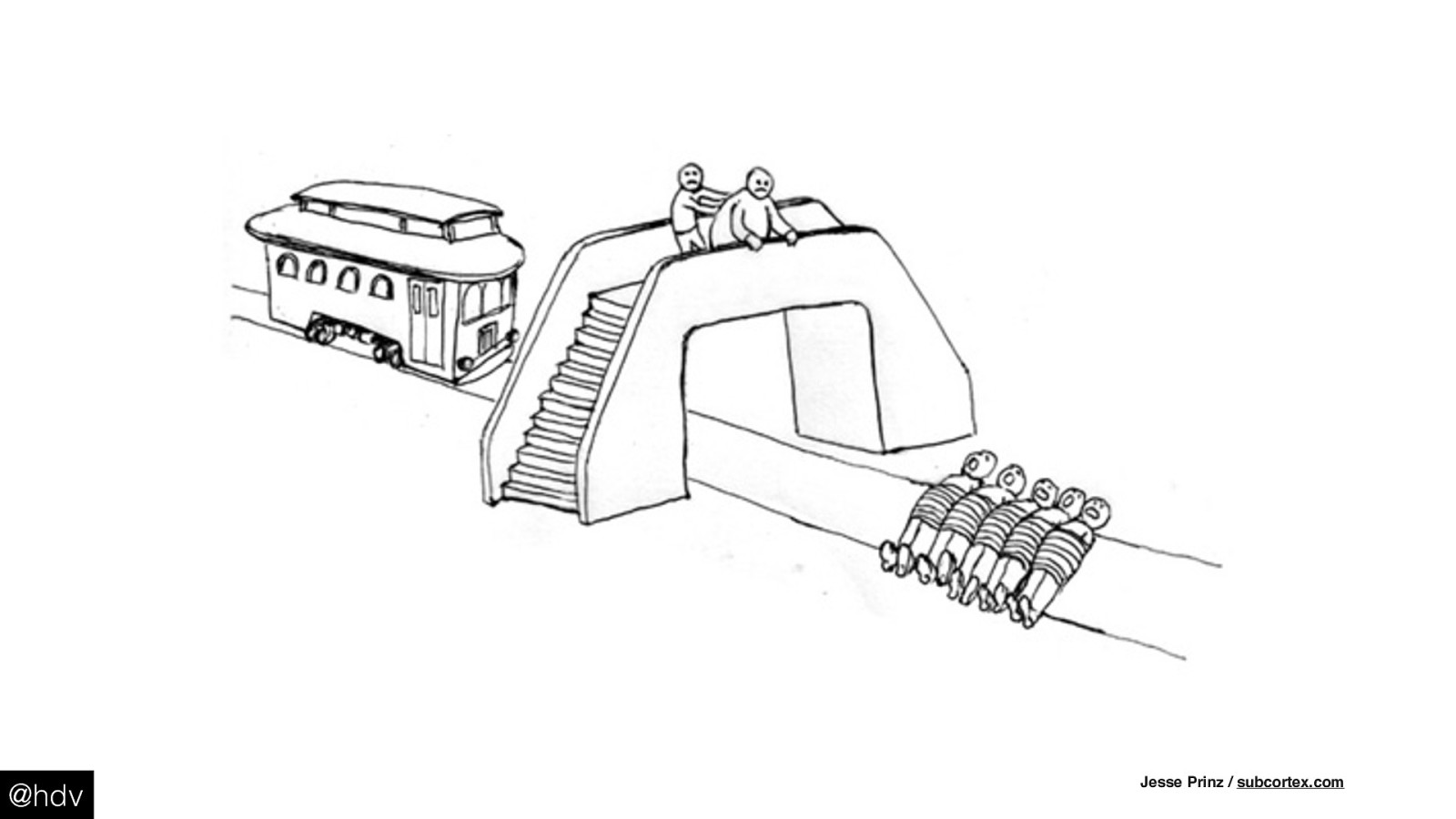

There is a variation on this, where there is only one track. A trolley approaches five people, who are tied to the track. You are standing on a bridge over the railway and you can see what is going to happen. The trolley is going to drive over those five people, and they will likely die. Now there is a man on the bridge and you are able to push him in front of the trolley. That would cause it to stop and save five lives. What would you do?

And what if the person you’re pushing was actually a doctor? Or a recruiter?

Slide 60

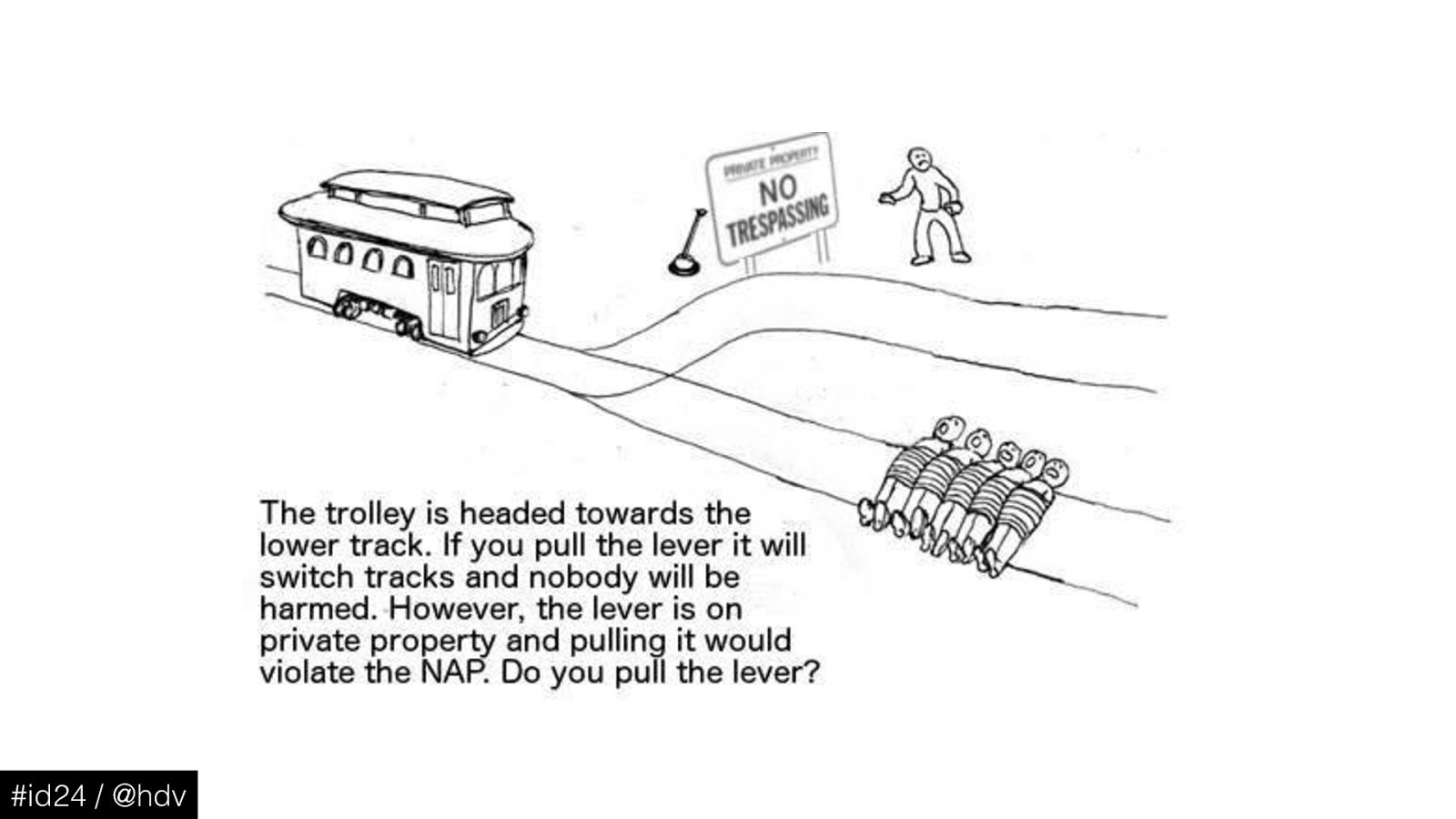

There’s also the libertarian variation, where there are two tracks, again, and you can pull a liver to divert the trolley, however now the trolley would drive onto a road that is in fact private property and has a sign ‘no trespassing’.

Slide 61

These examples are all about making the right choices, it is about making the right decisions.

Slide 62

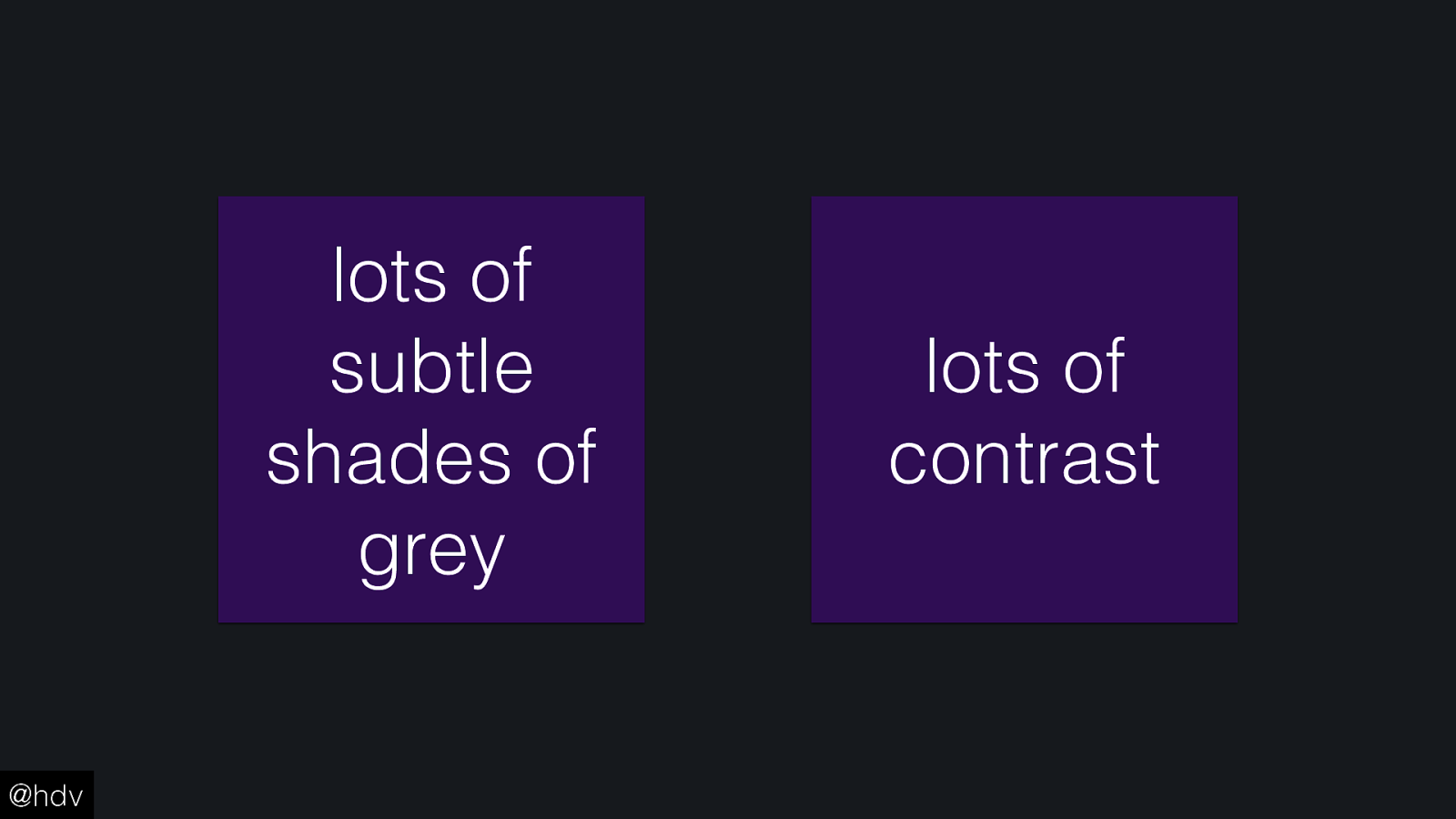

For example, maybe one of your team members love subtle. They love to go to restaurants with subtle names, wear subtle clothes and have subtle art on their walls. When they design an interface, they also like to use subtle shades of grey on a black background. It looks beautiful.

However, there might be another person who cannot use the subtle interface, because they are working on a train, their computer is on battery power and the brightness is set to low to save energy. They require contrast.

What do you do?

Slide 63

The good news is, in web accessibility, you do not need to kill either of these people.

But as you will likely only build one interface, you will need to choose between having lots of contrast or going for subtle.

Slide 64

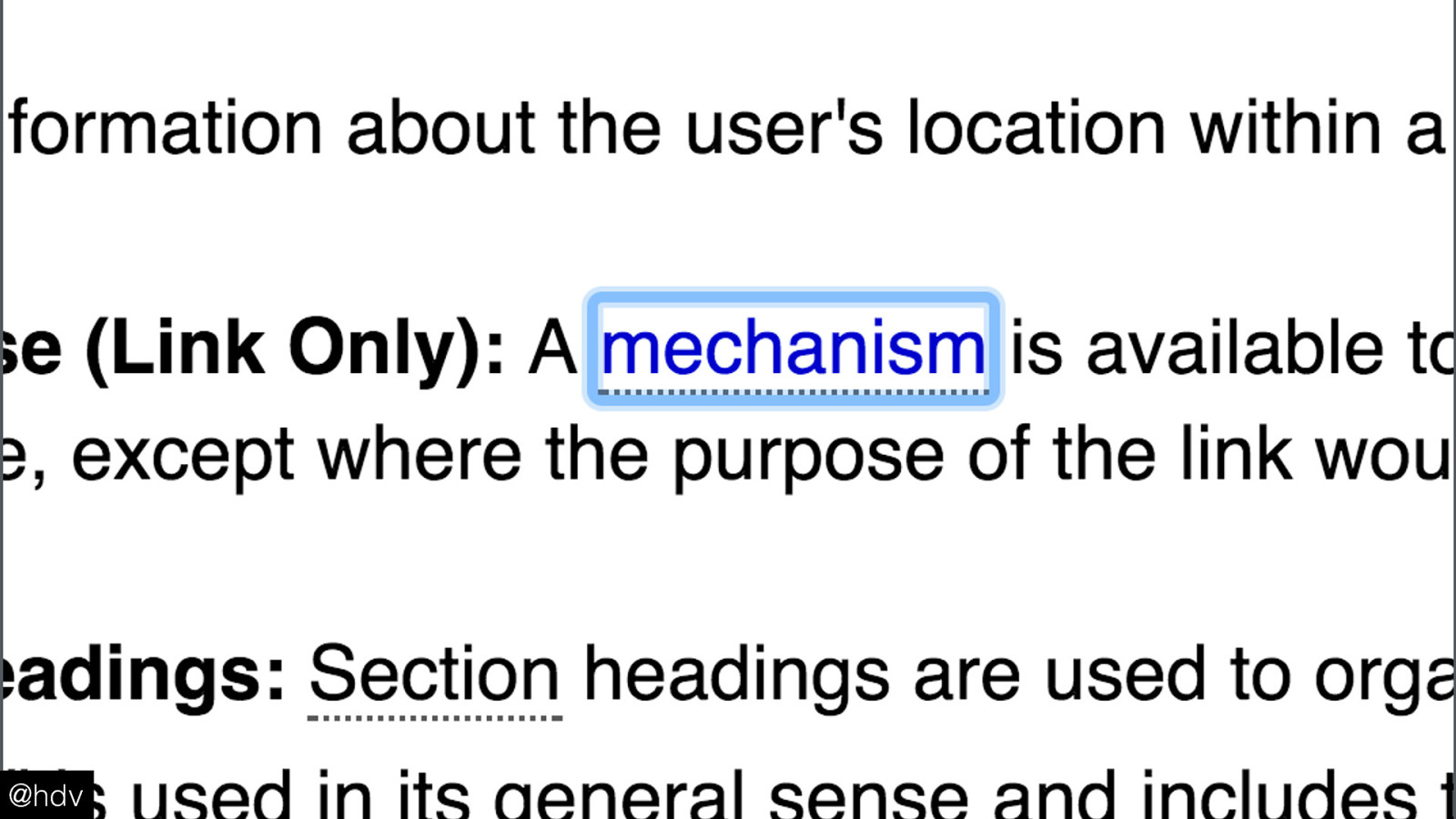

In this screenshot you can see a link that has focus. These so-called focus outline are used by people who browse the web without a mouse, for example by means of a keyboard.

This is an example of what that looks like by default in the Safari browser. If you don’t like the way this looks, you can choose between two solutions.

Slide 65

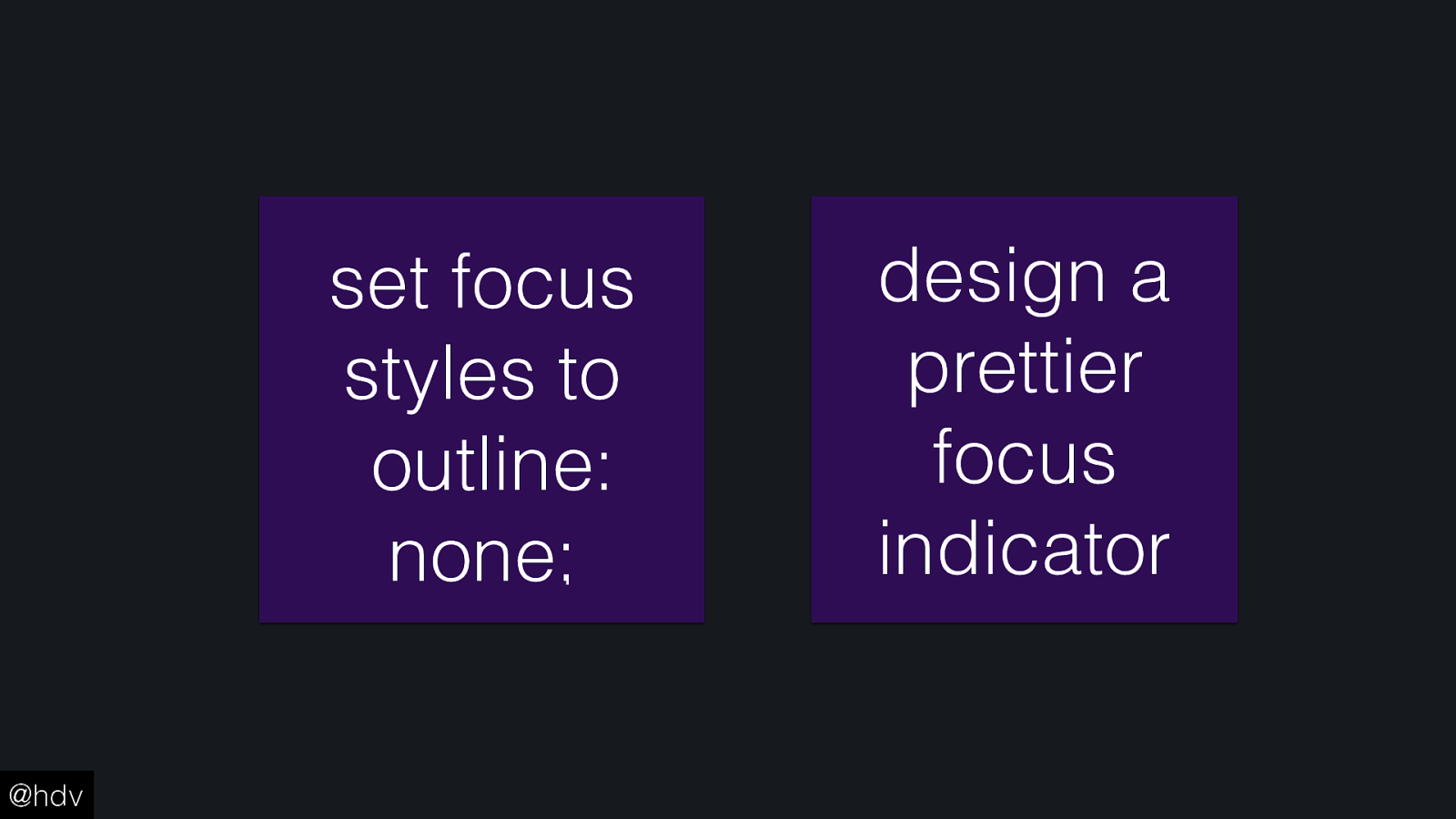

You can set focus styles to outline: none in CSS. This removes the outline all together. But this makes the site unusable to some of your users. Or you can design a prettier focus indicator.

Slide 66

As a web team working on digital interface, this is a lever you can pull! You can choose to make inclusive decisions. Consider how you can make your product usable for as many people as possible.

Slide 67

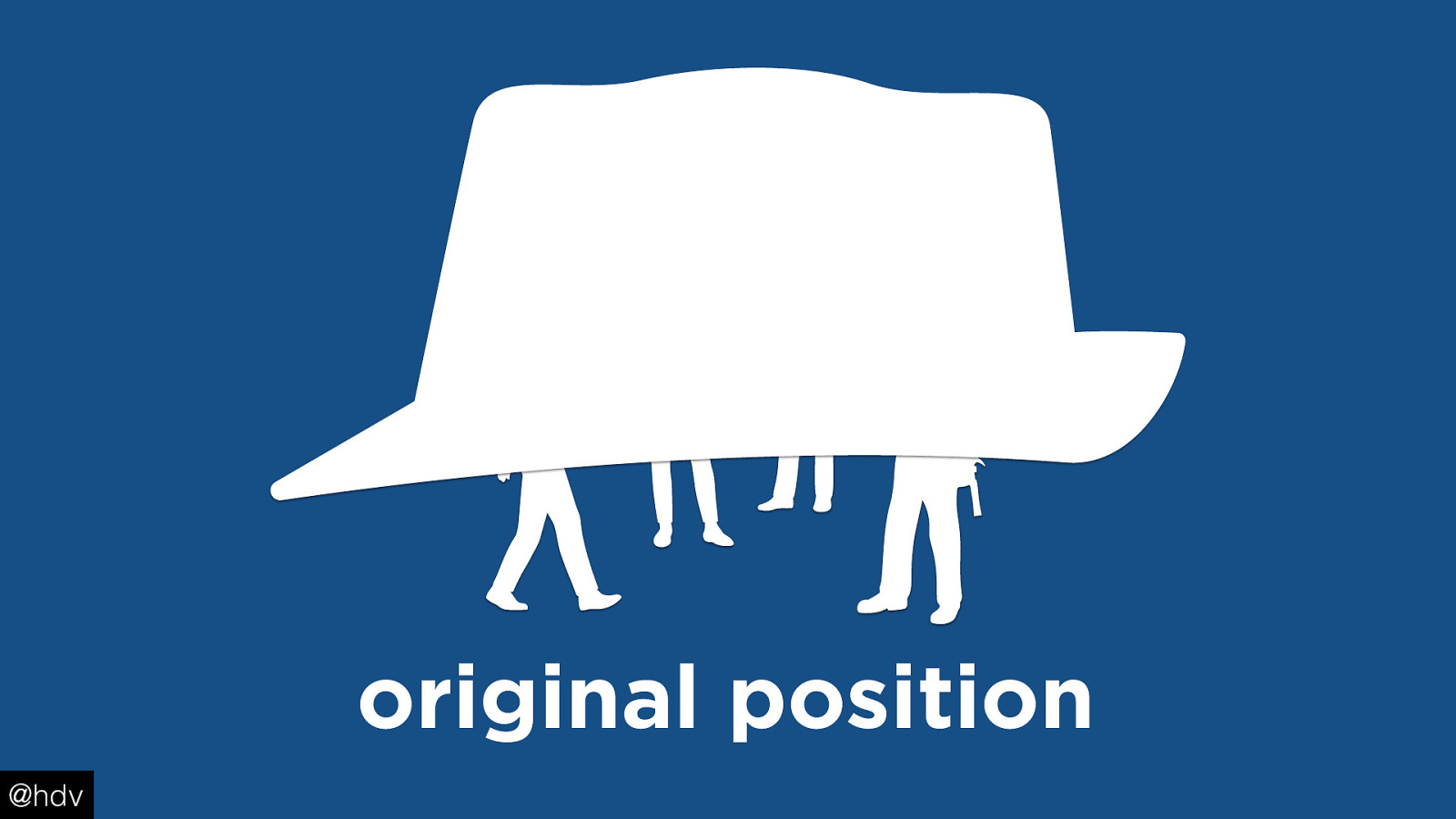

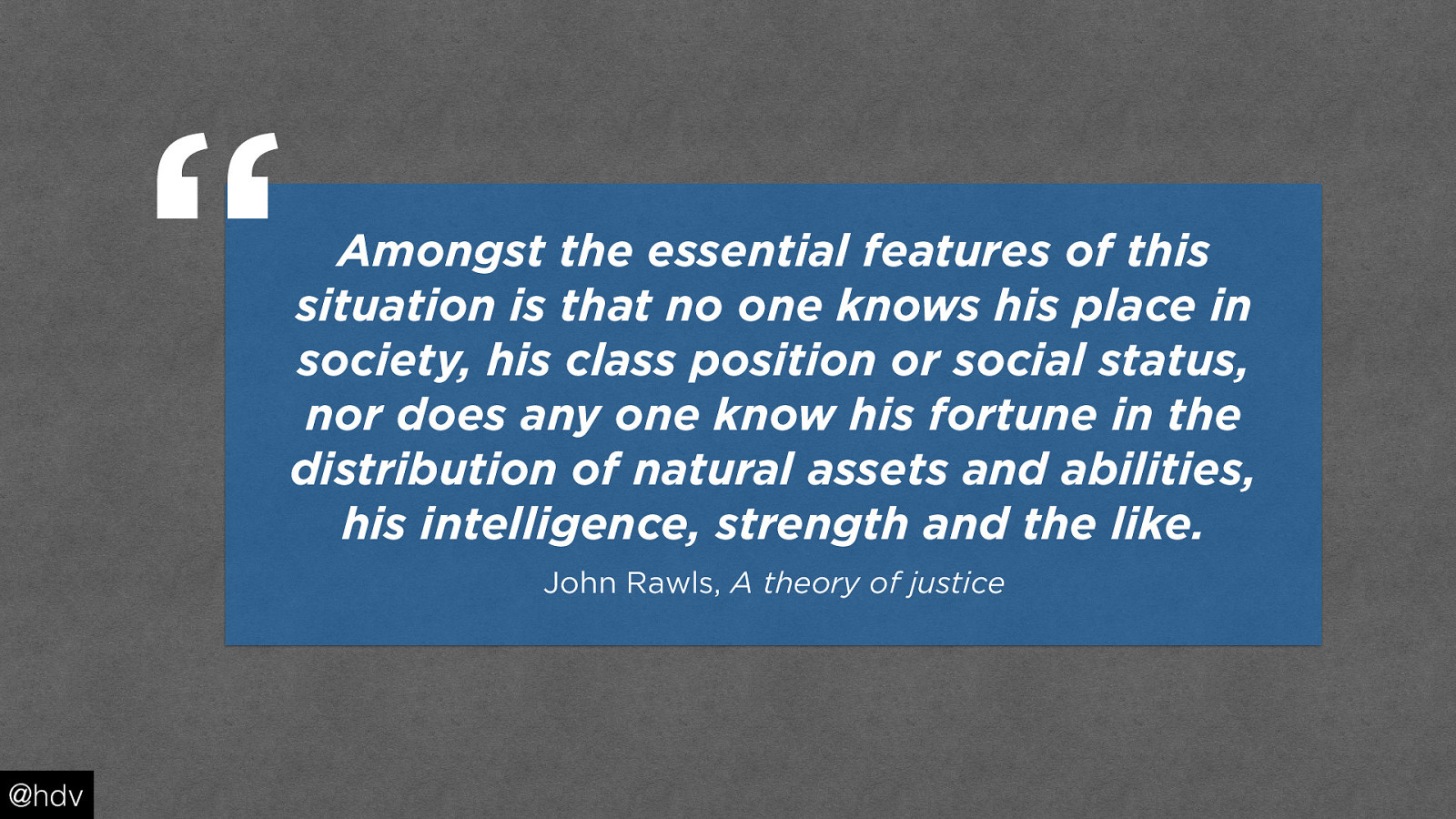

Here’s the second example, John Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance, also known as the Original Position.

Slide 68

Imagine a group of people is asked to come up with the fairest way to organise society, they can distribute wealth and justice in any way they would like.

Slide 69

However, they are under a ‘veil’ and have no idea what their position in live would be. Rawls calls this the “original position”. They wouldn’t know if they would live as a CEO of a multinational, as a care worker, or as the King. The theory is that without this knowledge, they can’t find solutions but solutions that are equal.

Slide 70

Another example to look at this, is distribution of passports and legislation around borders. Borders are among the largest causes of inequality word wide… here in Europe we have passports that allow us to enter almost any country without a visa… there are many countries worldwide where people have to apply for visas for most trips abroad, including (or especially) trips into Europe.

Applying this to Rawls… if you had a group of people decide about rules for crossing borders, but take their passports away from them, then distribute them randomly after they’ve come up with the rules, you’re likely to get rules that are fair.

Slide 71

So, when people are put “in the original position”, wearing a “veal of ignorance”, they are likely to pick solutions that treat everyone equally.

According to Rawls, two principles characterise the solutions people come up with when they are put in this original position.

Slide 72

One is the principle of equal liberty, this is what I mentioned before, people in the original position are likely to pick solutions that distribute freedoms equally.

Slide 73

And there’s also the difference principle: if there is any inequality, this can be just, as long as it causes the least advantaged person to still be better off than without the inequality.

Slide 74

This case is about taking away any advantages (or disadvantages) we have from our reasoning about how we should do things. When thinking about our digital projects, we should think from the original position. To put it bluntly: leave any privilege at home.

Slide 75

Think beyond your own retina screen…

Slide 76

…beyond where you were born…

Slide 77

…and beyond your own fast office WiFi. If you suffer from no colour blindness, leave that fact out of any arguments about colour choices.

Now, I’m not claiming any of you have any of these advantages, but you’re likely to have some advantage, and the point of this example is that leaving those out of decision making will make our products more equal to all.

Slide 78

This example isn’t really from philosophical ethics, it is from game theory, which has its origins in computer science, mathematics and economics. Let’s look at it anyway.

Slide 79

Two members of the same gang are taken to prison, and they have been locked separately, with no means to contact each other. They are in separate cells.

The prosecutor’s don’t have too much evidence against them, but enough to put them away for 1 year each. However, they decide to offer them a one year reduction, if they betray their friend. The friend would then get 3 years in prison, and they would walk out free. If they both take up on the offer, they would both get 2 years.

Slide 80

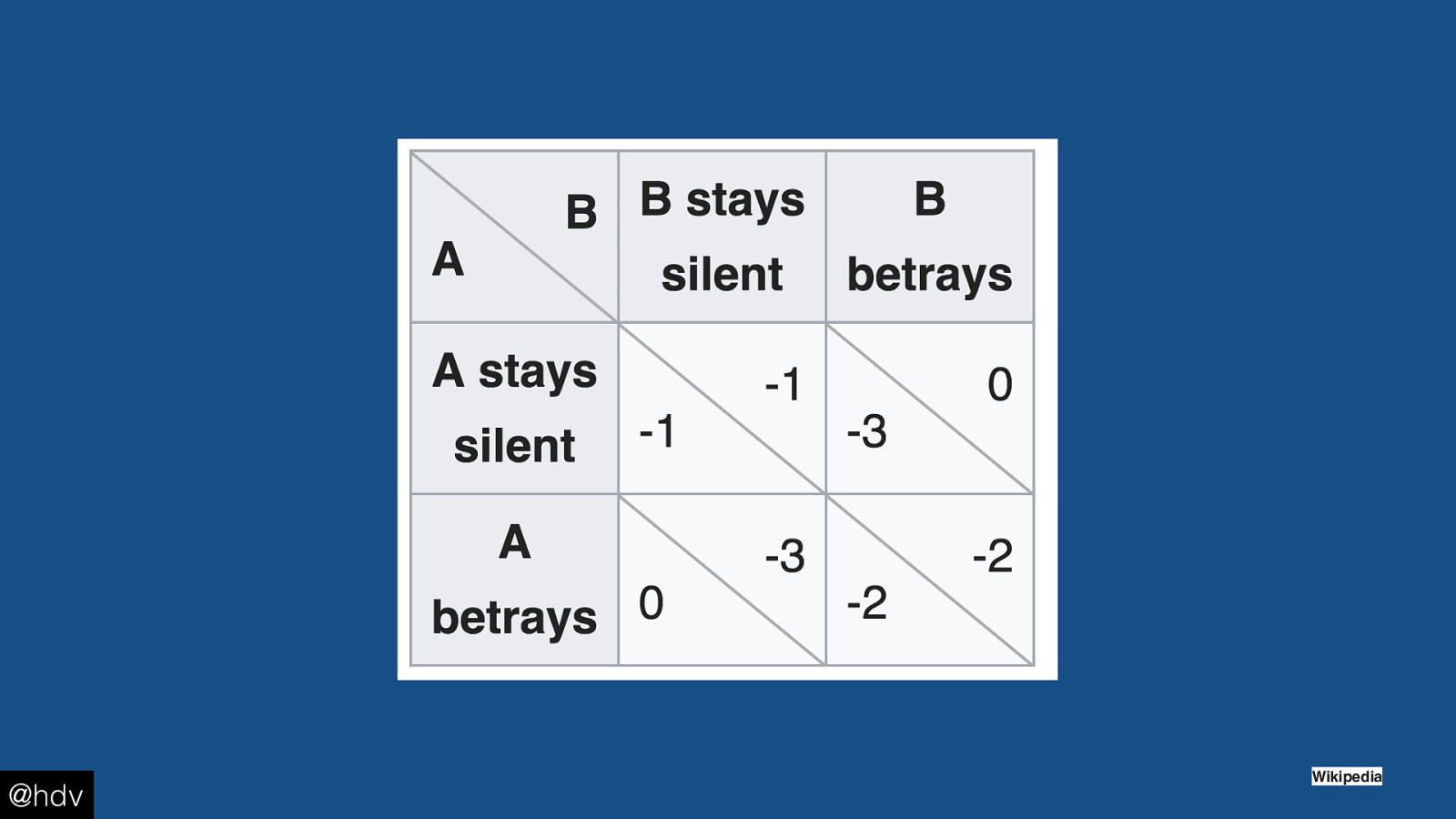

The matrix looks something like this. Betraying gives more reward than staying silent, unless they both betray, in which case they would both be worse off.

Slide 81

So you could say this problem is about conflicting interests that are leveraged unexpectedly.

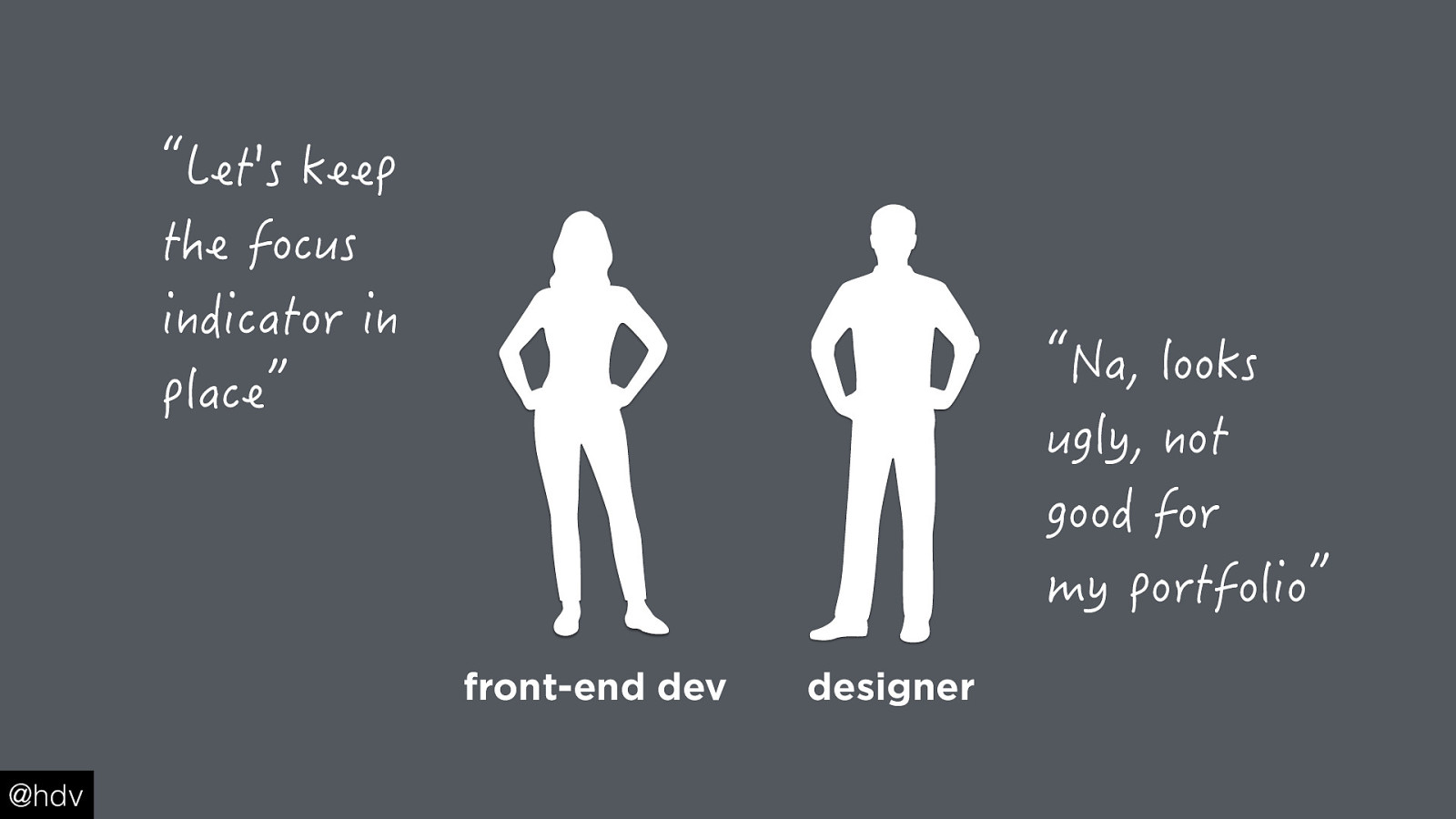

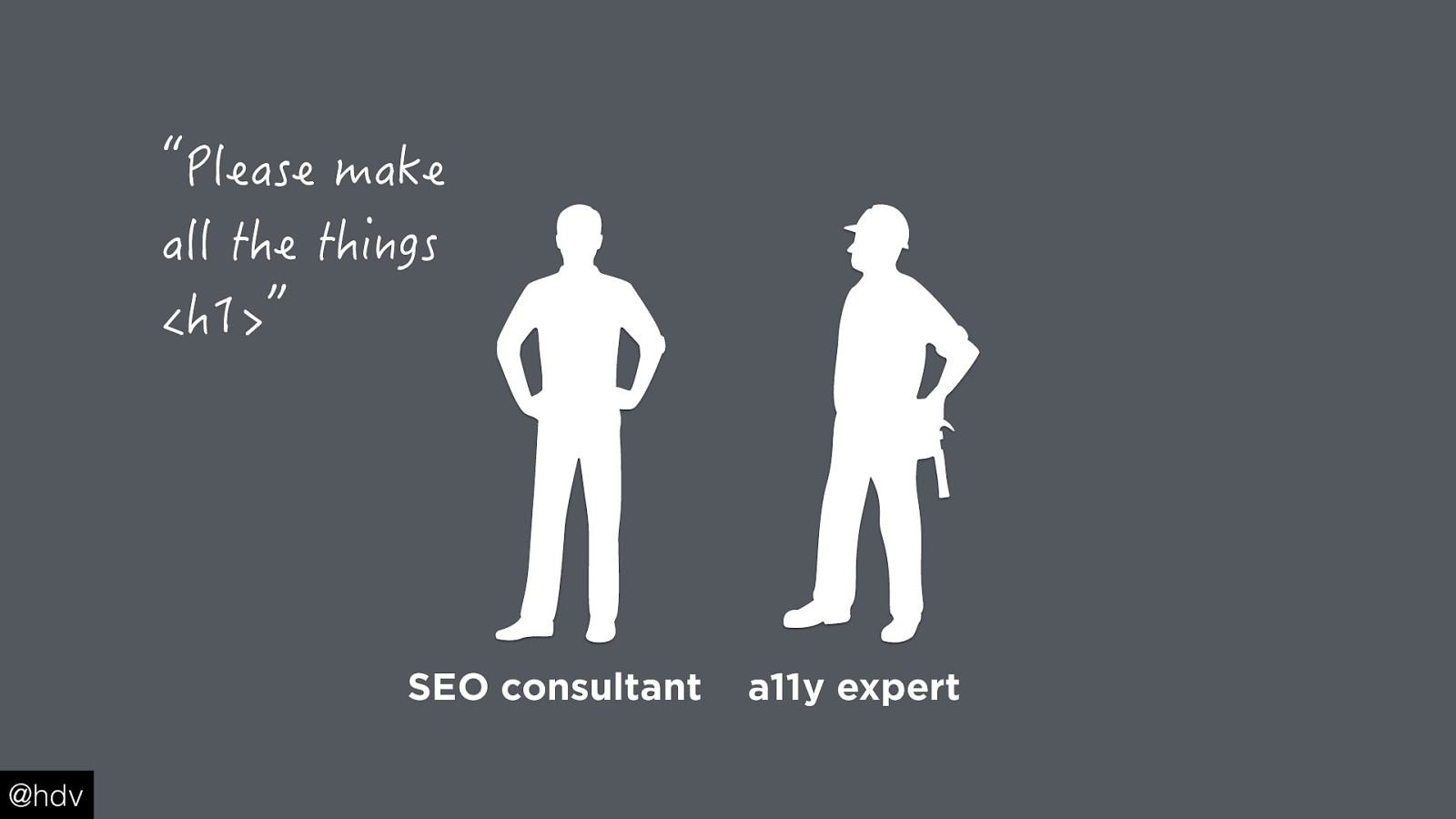

We have lots of interests in our projects, don’t we? I have gathered a couple of conversations that I have seen in my work. They might be familiar.

Slide 82

In a project I worked on, the front-end dev said “Let’s keep the focus indicator in place”.

Slide 83

The designer argued against this, it wouldn’t look good on their portfolio.

Slide 84

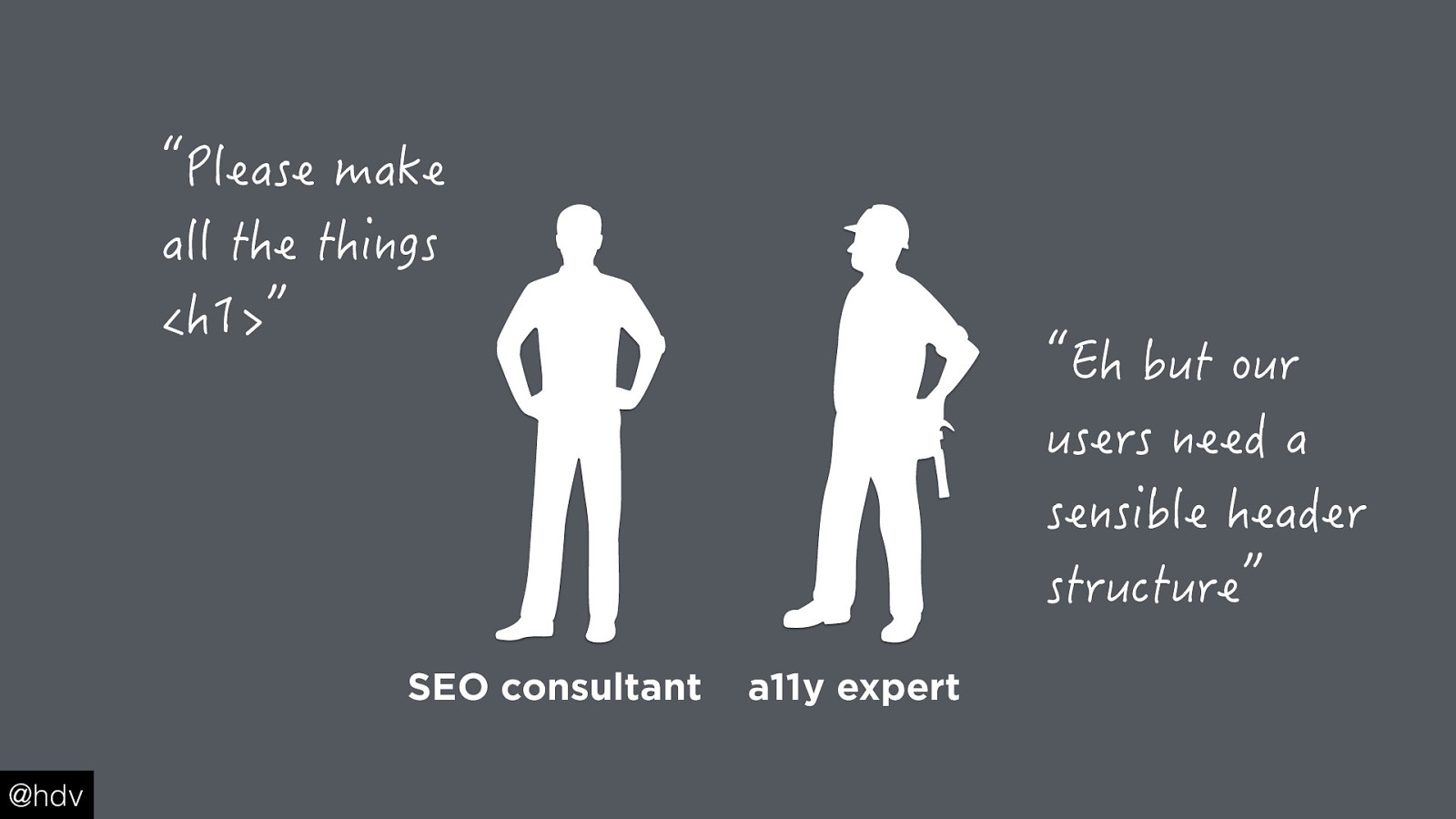

Maybe an SEO expert claims the team should only use top level headings, because they assume it improves search engine rankings.

Slide 85

An accessibility expert might disagree, and would argue to keep a sensible header structure as that benefits some users.

Slide 86

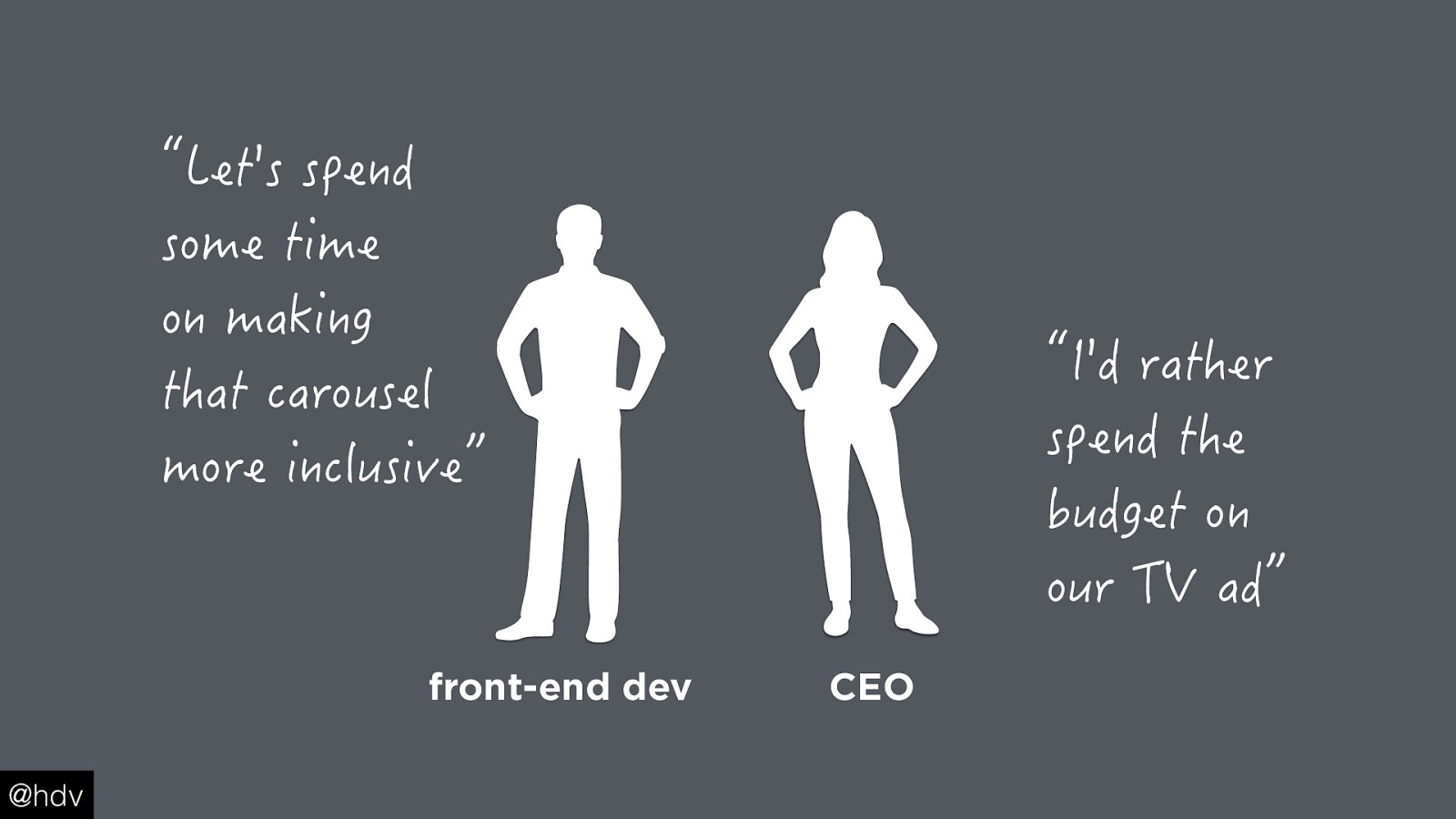

Maybe your front-end developer wants to spend some of the last budget on trying to make the carousel on the homepage more accessible…

Slide 87

…while the CEO feels more like spending that budget on a TV ad.

Slide 88

Interests and knowing about them can also work in our advantage. Sometimes lining up interests can be a method to achieve web accessibility. It isn’t my favourite way to argue for accessibility, but… with the new Europe-wide accessibility legislation, governments and others have to follow WCAG2.

Making it accessible costs exponentially more when done in retrospective, it is cheaper to bake it in from the start.

Slide 89

A good way to line up interests is to make a business case. This sounds boring…

Slide 90

But it is not, as is proven by Alice Bartlett’s fantastic talk about this at Fronteers 2015.

It’s good for us people who make websites to learn and speak the language of people who pay for them. Also if we want to argue for accessibility.

Slide 91

Another great resource about making the business case for web accessibility, is on the WAI website: https://w3.org/WAI/business-case

It has lots of useful examples.

Slide 92

So to go back to the prisoner’s dilemma… the prisoners cannot communicate. In the real world, you can often see the other person.

Slide 93

They aren’t locked somewhere, you can go and talk to them. Or at least figure out about their motives and their interests.

I’ve found this is a great way to get accessibility done in the places where I work. There are always overlapping interests, and they can be used to promote accessibility.

Slide 94

Ok, those are the three thought experiments I’ve wanted to share with you today.

Slide 95

So, in conclusion, when stretching the examples all the way from their original meaning towards a plan for more accesibility, these are my three takeways.

Slide 96

Make good choices, choose the inclusive thing. Divert the trolley into the inclusive direction and you don’t even have to kill anyone!

Slide 97

Treat people equally. It’s really important to forget about what we personally experience in order to make something that works truly for everyone.

Slide 98

Line up interests! Figure out what the interests are of the people who are blocking you from making accessible products, if there are any.

Slide 99

That’s all for me today, please feel free to contact me on email (hidde@w3.org) or Twitter (@hdv), look at my page (w3.org/people/hidde) or find the slides online (talks.hiddedevries.nl).